Part 1

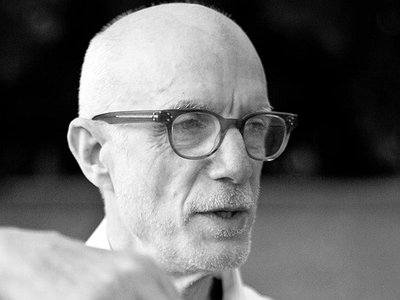

Name: Jeffrey Roden

Occupation: Composer

Current Release: Threads of a Prayer Volume 1 on Solaire

Recommendations: Witold Lutoslawski, Ernest Hemingway

Website: If you enjoyed this interview with Jeffrey Roden, you can find more information about him on his website.

When did you start composing - and what or who were your early passions and influences?

In the beginning I had no conception or illusions about becoming a composer. I began writing music that featured the electric bass in the mid 1970’s. In hindsight it is evident that what I wanted to accomplish required a new music. Among my first realizations was that any emphasis on rhythm had to be eliminated or the bass would be restrained by its usual function. The reduction of the importance or the actual elimination of rhythm was to become a central feature in all my work going forward. I have arrived at my current position by virtue of my doggedness and willingness to follow wherever the arrow pointed.

As I am essentially self-taught, I have had no real influences other than hearing music that I enjoyed. I have never made a great deal of effort to analyze or study other composers’ work other than by listening. Even now I discover composers that any reasonably well educated person would be very familiar with. An example of this would be Witold Lutosławski. My influences are completely out of synch with my work and I have no explanation for this.

For most artists, originality is first preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you? How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

For better or worse I have always had my own voice. This personal sensibility was particularly difficult - even painful - when I played the bass for a living. It is one of the many reasons I ended my professional career. To compensate for that struggle, I have been fortunate in that all my teachers have been content to impart the technical and professional knowledge that was necessary at a particular moment without ever infringing on the personal nature of my work. I feel very indebted to Ian Krouse as he has provided a great deal of knowledge without injecting his own sensibilities into the conversation. If I have tried to emulate anything, it was the feeling that the musicians and composers I admired delivered in their work. In some ways, there has been a distinct advantage in not having had my vision or work tampered with by exposure to history or academia. I sought to emulate through my own vision the feelings that moved me in other musicians’ and composers’ work.

What were some of the most important creative challenges when starting out as a composer and how have they changed over time?

In the beginning, a sheer ignorance of the technical information that most composers would have at their fingertips. This lack of knowledge may have actually turned out to be quite a positive thing. I began composing music for the solo piano which led to a series of decisions from which all my music has undoubtedly emerged. The music for the piano created a template and guide. The guiding principle was an awareness of how little material could carry a moment and convey a range of expression.

It was also very difficult to remove the aspect of complexity and to redefine what exactly virtuosity is. This is more a question of courage and confidence in the material. When you realize that there are entire books written on violin technique, it causes you to either never start orchestrating, or to write music that uses the various instruments in their most basic manner. This is very closely tied to my work for the bass where I use the most standard of all electric basses without any of the modern devices, techniques, or tuning. The difficulty is always in the choosing and once you start to choose, things roll along without you.

Tell us about your studio/work space, please. What were criteria when setting it up and how does this environment influence the creative process? How important, relatively speaking, are factors like mood, ergonomics, haptics and technology for you?

I have lived in so many places that the space has less and less influence on the work. However, in our house in Los Angeles the music room was quite special. I have no understanding of why. The room is filled with memories, photos of people, small objects from childhood; an environment of familiarity. This also includes objects that serve to remind me of my intention. For example, I have a wonderful picture of Mary from a church in Venice prominently displayed on my piano. Her statue has stood in a church for some number of centuries and provided the viewer with something of value. This is a worthwhile intention.

The only part that technology plays is that I score using Sibelius software. I make a point of not recording anything, even sketches, as the recordings tend to overshadow the composing process by virtue of the fact that the recordings start to take precedence over what is being written.

I would love to live somewhere permanently where I could fill one room with my work for the rest of my life. This is a continuous dream but whether it would be beneficial I cannot say.

Could you take me through the process of composing on the basis of one of your pieces that's particularly dear to you, please? What do you start with when working on a new piece, for example, how do you form your creative decisions and how do you refine them?

Generally, I begin work at the piano and try to find a melodic phrase, chord, or harmonic progression with which to begin. Once I find some tiny bit of material that interests me, I extract a series of notes that become the basic vocabulary of the piece. This sounds very formal but it is anything but. The process generally begins without my having a subject matter in mind and inevitably some feeling or thought is brought to my attention that the piece becomes centered around. ‘The Many Latitudes of Grief’ would be the exception, as it was composed for a specific person and purpose. I gradually find pieces of material that connect as a whole; from there a rough draft emerges that can be played completely at the piano. This rough draft enables my moving forward with the confidence of a clear path from start to finish. At this point I begin to think about orchestration and move from the piano to Sibelius. Here almost anything can happen as I am away from an instrument and dealing with only possibilities. The piece I am working on now has had the entire ending moved to the beginning and many of the parts in the middle have been subjected to similar surgeries. In the first stage at the piano I am still slightly a musician whereas when I move to Sibelius I am devotedly a listener. I tend to labor over each section individually and then spend an equally grueling amount of time making sure the whole piece moves along without any distraction or loss of focus. I have no clear idea of why the work is right or when it should end. I only know when those moments occur. One of the most important lessons I have learned from Ian Krouse is to listen for what should be repeated or extended / developed. It is so easy to rush through a moment without extracting its full worth and beauty.