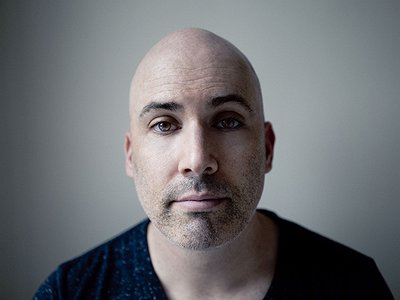

Name: Andrew Shapiro

Nationality: American

Occupation: Composer, pianist

If you enjoyed this interview with Andrew Shapiro, visit his official website which offers plenty of biographical information, links to his socials as well as a store for his albums and sheet music.

Music can heal and music can hurt. Do you personally have experiences with either or both of these?

For sure.

At Conservatory, they made us sing in the choir and one piece we performed was the Requiem by Gabriel Fauré. It’s an amazingly beautiful and wonderous piece of music and I always felt uplifted while rehearsing and performing it. About two years later, in the immediate days after 9/11, I was flipping around on TV and there it was, being performed at New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral televised worldwide. It sent a soothing balm through me.

One of my favorite bands is the Cocteau Twins and their distinct soundworld is of great fascination to me. Their music is soothing, but it’s not only that. It’s also as if the music is saying, “We know, we know, you’ve had rough times and so we’re acknowledging that – and validating that – and we’re also going to soothe you before you turn around and go back out into the world again.”

Regarding music hurting me, it’s more that things around music have hurt me. Many people like me went to Conservatory majoring in music composition and wound up in a harsh and strange world. I felt pushed into writing music I didn’t really want to write; it seemed like nothing anyone ever wrote was good enough, academic enough or “interesting” enough. I recall a time when I was telling one of my teachers about a Grateful Dead song I was really into at the time and how for a long stretch of it was just an E major7 chord for two measures and then an A major chord for two measures. And that repeated for quite a long time. I loved it. And his reply was belittling: “that sounds boring.” That kind of thing messed my brain up for a pretty long time.

There was this total lack of regard for the concept that people might not all be trying to do the same kinds of things with their music. I started calling the kind of music they wanted from us ‘Composer Concert Music.” Later on I was finally able to internalize that it’s really easy to write complicated/academic-styled music. What’s hard to do is write C major and really mean it.

We are still in the process of learning how music influences our body and mind. What are some of the most important findings in this area from your point of view?

Of course, people have a track they put on to get them pumped up to exercise or before they go out to a party or something. I remember in Morrisey’s autobiography he said he used to play a certain Bowie track before going to school so he could get through the day. Music now, via playlisting is about the mood of course. “Focus Music” or “Reading Music.” I was surprised to see online someone had written “Andrew Shapiro Pandora Radio makes doing homework so easy” and “Andrew Shapiro Pandora Radio is the best station to write a paper to.” That was unexpected and fun.

So, from my point of view, the most important findings I’ve had are when people are kind enough to share with me their anecdotes about how my music has influenced them. I get all kinds of messages from people and one was from a guy facing a medical problem and he had to have an MRI and it was thought he might have a very serious heart problem. And he said during the test and while waiting for the results he listened to my piece “Mint Green” on repeat because it was the one track he knew of that would help soothe and comfort him and provide him with some kind of stability during an incredibly stressful time. It was a high honor for me; I created something from nothing and it totally helped him. Fortunately, he turned out to be okay.

In an interview for Psychology Today, you already hinted at the experiences which lead you to minimalism. I could have imagined other styles of music fulfilling a similar aim – my own path also led me to minimalism, but coming from a very different angle (electronic sequencer music), for example. Why, do you think, was it precisely minimalism that felt 'right' to you at the time?

The angle I was coming from was that I grew up as a serious classical clarinetist and studied the major genres of classical music like Stravinsky's Primitivism, Brahms’s Romanticism and Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto. I had also played in orchestras, wind ensembles and chamber groups as well. And I played saxophone too, which led to session work, jazz combos, big bands, pit orchestras, and pop/rock and funk bands. And so, by the time I got to music school I was pretty well-versed in a variety of different styles.

But minimalism was a totally new and exciting thing for me. It’s a hybrid of classical and popular sensibilities which is where I had lived my entire life. The people making it were still alive. It was American and it was happening in New York where I’m from. From the get-go it was a very, very comfortable place for me to be.

The minimalism of, say, what Philip Glass was writing in 1998 – to the extent that it is minimalism – was also something that showed me opportunities were there for creating music that could find an audience. It lent itself to so many different settings like theater, film and advertising. Music was being licensed into big TV commercials because brands wanted the psychology that came along with the sort of hypnotic spell cast by this musical language. I saw the potential for a sustainable career which I certainly didn’t see in the post-war classical academic world.

You studied at Philip Glass's studio. What's your impression of how Glass saw his own music in this regard? What were some of the creative aspects that you took away from that period?

Well, my life changed the second I walked in the door. Philip’s score for Martin Scorsese’s film Kundun was up for an Academy Award, they were recording music for the Jim Carrey film The Truman Show, and a million other things were going on. How could one not get pumped up being around this energy? Philip paved the way to get out of that sort of music school composer mentality. He showed you could achieve high art with popular music underpinnings; that you could have that simultaneity that certainly didn’t exist in conservatory.

I went over to his house a few times and showed him some stuff I had written. But what was more valuable was when we sat at the piano together and he explained his way of creating his harmonies. He said, “If you’ve got interesting harmonies you can do your figurations any way you want.” His chord changes are full of breathtaking flexibility and complexity where he’s so fluent at toggling chord changes around and making it seem so accessible. In school we never talked about a F7 chord resolving to an E major chord because it belies everything that we learned about the harmony of the late baroque era or the classical era.

Popular music harmony plays a big role here. Years later, I learned about something called neo-Riemannian theory. In simple terms, it’s the idea that so-called regular triadic harmonies can relate to one another without reference to any particular key. And within the movement of one chord to the next there are a variety of half-step motions (particularly when minor, major and diminished 7ths are added) that can propel motion and generate a sense of freshness and revelation. This was Philip’s underlining harmonic ethos and it inspired me to begin my own searching in this realm.

A great place to hear this is in the score he wrote for the film The Hours which, for me, was the final nail in the coffin of the artificial divide between art music and non-art music that existed in my mind. And I told him my whole “final nail in the coffin” bit and I could tell he was quite flattered.

The interesting thing to me is that minimalism is often portrayed as bringing back an element of simplicity into composition – on the other hand, quite a lot of his music is only simple on the outside. Tell me a bit about how minimalism in life and music can contribute to mental health, please.

The term ‘minimalism’ can mean different things to different people. When someone clears out their closets and drawers of unwanted clothing and pares down their book collection and gets rid of furniture — gets rid of everything they can — this is sometimes described as being minimalist.

But I was introduced to the term as a description of a movement in the visual and musical arts from about 1965- 1980. There were a number of artists, mostly in New York and on the West Coast who were making a new kind of work which really seemed to embrace the reality that there was virtually no money or support for what they were doing. And so, if you don’t really have any resources, what’s the most practical way to express your ideas? One way is to reduce things down to the absolute barest essentials, or simplicity as you say. For instance, a sculptor might take 8 blocks of wood and lay them down next to one another in a certain way. That’s affordable. It’s also really severe and pure and is what is now considered to be minimal. Playing scales and patterns or drones can also be a way of expressing a lack of resources.

Now where’s the analog between minimalism and mental health? There are many, but one quick example is that in Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) there’s the idea that if you’re feeling dysregulated, or very anxious or whatever you want to call it, you can do something as simple as taking a cold shower. Or you can dunk your head into a bowl of ice water. It can have a huge effect. Cold water can change your body chemistry and shock your system. And it might very well be enough to get you out of your undesired headspace and bring you into a more regulated one. You don’t really need any resources. All you need is a shower or a bowl with ice water.

You just took part in a panel discussion including Cary McQueen and Beth Killian. What is your impression of the response of the professional psychology community to your ideas?

I can’t speak to the response of the ‘professional psychology community’ because I’m not aware of any response whatsoever. There are a number of people who work in mental health and/or the intersection of the arts and mental health that I’ve reached out to and they have been interested in writing about the concepts fueling certain projects of mine or have invited me to participate in panels or whatever to talk about the psychological underpinnings of my work. My genre of music and my personal soundworld relates to mental health as it can be heard as soothing, and something positive. I’ve often been told or get messages from all over that say there’s a relaxing quality to it and that it can promote mindfulness.

When it comes to the healing properties of music, in which way do you actively try to incorporate them into your music?

I’ve never once thought, “Ok, I’m going to write a piece of healing music right now” or “I’m going to write a soothing piece of music right now.” It’s more at a deeper level whereby I seem to just automatically gravitate to “I’m writing a piece of music right now and the process of writing it itself is what is soothing and healing and supportive to me.”

But as a performer, one has the opportunity to give this gift to the audience and so whether it’s 1000 people or 50 people or even one person I’m playing for, there’s a kind of wavelength that I try to tap into so I can connect deeply with the audience. It can become a tangible thing and everyone in the audience and performer unite as one thing and that has the makings of a great experience.

My song "Atlanta" is about my first year of college in Atlanta. It was a terrible year and its legacy stayed with me for a long, long time. I knew I wanted to write a song about it; about the way the floor fell out from under me and about how I just ran out of gas trying to be a certain type of person and how I fell into a deep depression. And the song is not just about that time but also about the legacy that that time left within me.

But how could I reduce this all down to a song? It could be a novel but I’m not a novelist. And also, it didn’t feel like it would be enough for me to just write the song. There was something in me that wanted to create a process whereby the creation of the song itself would give me my own mental triumph over the topic that prompted me to want to write the song in the first place!

That’s a very tall order. It was sort of like an incredibly complicated math problem or proof or something like that. I played around with it for years while living with the hurt and when I was finished, it was like the chunk of my consciousness that was hurting from that episode evaporated.

What would be suitable new approaches for appreciating music – from concerts to albums and new forms of listening – which could transport these qualities to audiences?

Maybe a one-on-one live stream performance? I’m sitting at my piano playing for one person. I do this for people sometimes. Dare I say this hints at one’s own private appointment with their therapist?

When it comes to the healing properties of art, many use the word spirituality. What does spirituality mean to you personally and how does it inform your work?

Another DBT term is “Participation.” Basically, it means that if you can figure out a way to get lost in the work or the activity you’re doing, you lose a part of yourself. And that for the time that you’re lost you can avoid emotional trouble because, in a sense, you turn into nothing; just pure consciousness. So, for me, I think I’ve always felt losing myself in composing, practicing and performing music is, if not a religious experience, it’s at least a quasi-religious experience and so one might swap out the word religious with spiritual.

Books, websites, articles or other sources of information recommended by Andrew Shapiro:

“Brick by Brick” is a terrific blog on Psychology Today’s website focusing on musicians and mental health.

The book "Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself" by Dr. Joseph Dispenza is amazing. The subtitle is “How to Lose Your Mind and Create a New One.” There’s also an accompanying meditation which I love.

James Breslin’s biography of Mark Rothko.