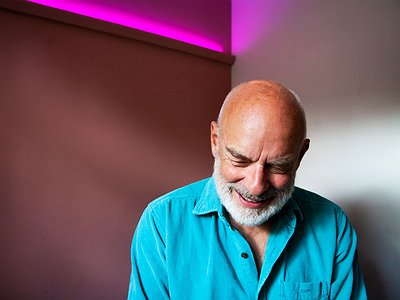

Name: Brian Eno

Nationality: British

Occupation: Composer, producer, sound designer

Current event: Brian Eno’s new album FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE is out now via UMC.

The essay below was compiled from a longer keynote interview at IMS Ibiza 2022, in which Brian Eno talked about his charity EarthPercent and "the urgent need for the music industry to tackle the climate crisis".

Ressources:

Visit the EarthPercent homepage

Visit the website of Friends of the Earth

If you enjoyed this interview with Brian Eno and would like to find out more, visit him on Instagram.

Over the course of his career, Brian Eno has collaborated and worked with a wide range of artists, including Hans-Joachim Roedelius, Michael Rother, John Tilbury, Roger Eno, Bang on a Can, J. Peter Schwalm, Tom Rogerson, and Jean-Michel Jarre.

[Read our Roedelius interview]

[Read our Michael Rother interview]

[Read our John Tilbury interview]

[Read our Roger Eno interview]

[Read our Bang on a Can / David Lang interview]

[Read our J. Peter Schwalm interview]

[Read our Tom Rogerson interview]

[Read our Jean-Michel Jarre interview]

Brian Eno: "People realize that if you're an artist, you're probably doing the job that you wanted to do. And I think that makes it's rather different if they speak about the environment. If a politician is asking you to do something you think: What's in it for them? But for artists, there's nothing to gain other than the thing itself. Nobody's gonna vote for me because I'm not standing for election. So there's a kind of faith that these are people who are doing what they want to do, and they've chosen to take time to do this.

What artists have always done is trying to imagine different worlds. Now that different world can be just a song. Or it can be a huge Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork. And the work of artists is to try to compress a world into a song, a little world that you can spend some time in. What does it feel like to be in that world? That's what art is always saying, What does it feel like to be in a different world? This one or that one? Or that other one? Which ones do you like? And that's the way how humans test the future and get a feeling for the future. By going into these little simulations of future worlds that we call songs, or paintings, or sculptures, or films, or whatever else.

Now, you can see how this is very clearly the case with books. When somebody writes a novel, what they do is they describe a world and then they describe some of the things that happen in that world. And you have emotional responses to it. You think, Oh, I don't like that. I don't think that's quite right. You have a set of moral and emotional responses to the worlds that are presented to you in a novel.

And that's how we rehearse and understand moral and emotional vocabulary. That's how we find out what we like. We don't generally do it rationally in the sense of sitting down and making scientific and philosophical deductions. Some people do, but most of us don't, most of us see things and we have feelings about them. And then those feelings guide the decisions we make.

So I think people understand that about artists - that that's the job. And there's a kind of certain level of trust that if that's what you spend your time thinking about, then it might be worth listening to you on that subject.

~

Did you know that only 3% of all philanthropic giving is for environmental causes? I think that is astonishing. And that's globally true. In England, for example, if you look at the list of the 1000 most well financed charities, the first climate related charity comes not in even the top 100. For instance, the Royal National Lifeboat Institute is a much more successful charity in terms of what it collects, than Greenpeace or Friends of the Earth.

Now, I'm not trying to persuade anybody against donating to the Royal National lifeboat Institute or the Institute for the protection of donkeys, which is another very successful one. But I am saying that we're in a crisis here, and it might be good if we started directing our resources towards that crisis.

Myself and a few friends in the music business started thinking. A lot of money goes through the music business. What if we could say to people in the business: “I'm sure you want to give something to charities that deal with environment. And I'm sure you're confused, because there are many ways of addressing this. What are the best? What are the ones that really work? What are the ones that make a difference? That will make a difference for a long time, rather than just the ones that we've all heard about and make you feel good?”

So we started thinking, perhaps there's a way of suggesting to the music business that rather than just giving a donation every so often, why not create an organization that collects a sort of tax, a tithe would be the medieval way of saying it, taken from a small percentage of the money that passes through all of the organizations in the music business. That's to say, bands, artists, tours, agents, lawyers, record companies, streaming companies. We'd say to each of them, look, what about giving us 1% of your take. And what we will do with that percent, is redirect it to the best organizations that are really making a difference.

Now, that second part is quite important, because it takes research. And it takes expert advice. And it takes looking around quite a bit. And it's not something that most people are going to be doing on their own behalf. We have a very good team of scientific and environmental advisors. And we've set them the task of saying we want to address five areas to do with climate change.

~

A very important one is climate justice. Which is to say, how do we acknowledge and deal with the fact that the people who are going to suffer most from climate change are the ones who had least to do with creating it. That's a serious problem because it gives rise to a lot of subsidiary problems like mass migration.

Another important one, currently being addressed very well by charities like planet Earth, is how do we enshrine these ideas into law? If ideas aren't enshrined in law, they quite quickly get ignored. This is really about lobbying at the macro level to kind of stop coal power stations being built and things like that. Client Earth is a an organization of 260 lawyers working for the environment, and we will take governments to court if they don't fulfill the obligations that they've signed up to.

For instance, France signed up years ago to a fisheries agreement, which they never enforced, they just let their fishing craft carry on doing exactly what they'd been doing before. So we took them to the European Court of Justice, and we won the case. So France was then obliged, fined and obliged to fulfill those obligations. So that's one of the things that law can do.

Another thing that law can do is to set out an infrastructure that makes things more likely to go in a better direction. Two members of client Earth, who worked in the German office, bought a small amount of stock in, I think it was Mercedes Benz. And then they went to the general shareholders meeting with their few dollars' worth of stock, and said: “We think that making diesel cars is a bad business decision. It's clearly not the way of the future. And we think that it's bad news for shareholders.”

So they they attacked it from a purely traditional economic position. The movement was carried in that meeting and the company stopped. In fact, the city of Stuttgart made legislation that diesel cars would no longer be permitted in the city. This very quickly spread to the car makers who realized that the page had turned on diesel. And all the German car makers, within a very short time said that they were going to start making diesel cars.

Another important thread is conservation of nature. There's an organization called Global Green grounds, for example, that looks at generally quite small conservation projects in different parts of the world. I was contacted the other day by a lady in Romania who's saving quite a big piece of forest in Romania. This is old growth forest. The point about old growth forest is that it's different from newly planted forest, it has a very rich ecology that involves lots and lots and lots of beings, lots of different types of creatures. So, planting trees is great, and we should do it. But it's much more valuable to save forests that already exist.

~

And the very last thing I should say, the last thread, not in terms of importance, but just on this list, is related to the music business. If we're going to talk the talk, we should walk the walk as well. If if we really do concern ourselves with how much carbon we're putting into the atmosphere, then, as a business, we shouldn't be doing that. I'm glad to say there are lots of musicians who are thinking about this now. And some of them have been very committed and have put a lot of resources into it.

Coldplay, for example, have a kind of permanent team of, I think three or four people who are working on the environmental impact of that band. So like everybody, they don't want to give up performing completely. They want to carry on, but they want to see how they can improve that process. One of the biggest issues with carbon emissions in regards to touring is not the tour itself, but getting the audience to the shows.

So if you think you're playing to a stadium, 100,000 people and they've all driven to your show, that's a big footprint, arguably quite a lot bigger than the footprint of getting a band and all their equipment there. So Coldplay are starting to experiment with ideas like setting up buses so that people are driven to the show and back home.

Billy Eilish is another artist who is really conscious that we can't talk about saving the environment if we aren't doing anything towards that goal ourselves. So we would certainly like to become a kind of advice center to say this is how it works."