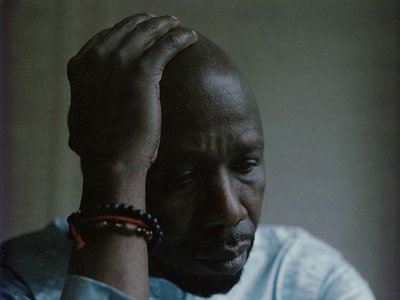

Name: Ballaké Sissoko

Nationality: Malian

Occupation: Kora player, composer

Current release: Djourou's new album Djourou is out now on Nø Førmat.

Recommendations: I am currently listening to lots of Indian music, such as Ravi Shankar. You can also play the music of the late Kasse Mady Diabaté.

If you enjoyed this interview with Ballaké Sissoko and would like to find out more about his work, visit his website or Facebook account.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I started to play kora when I was very young. My main influence is my father who was also a kora player. Lots of renowned musicians and singer from Senegal, Gambia or Guinea Bissau used to pass by our house to rest and play music in our yard. Our place was a crossroads where musicians stopped before going to record or perform in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. I was immersed in the music.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

I’ve always learnt to observe and listen carefully to others, to understand their way of playing. I used to sit in silence for hours listening to my father play. It helped me to adapt myself to different genres of music and instruments.

When I joined the National Instrumental Ensemble I needed to listen to many instrumentalists from all corners of Mali. Later I could play with musicians from other cultures. I’ve started musical collaborations with new sounds and instruments such as Indian sitar, flamenco guitar, piano, cello, oud or valiha.

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your creativity?

My identity is rooted in the Mandinka’s culture, traditions and philosophy. It’s all about dialogue and respect: the art of being yourself and being with others.

What were your main creative challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

Once you acquire technical skills, you need to constantly reinvent yourself and to find other variations of playing. As the saying goes: One must not keep his instrument in its barrack.

My creative challenge is to get the kora out of its natural environment and background - in order to explore new repertoires.

As creative goals and technical abilities change, so does the need for different tools of expression, be it instruments, software tools or recording equipment. Can you describe this path for you, starting from your first studio/first instrument? What motivated some of the choices you made in terms of instruments/tools/equipment over the years?

My kora remains basically unchanged through the years. We like its natural sound.

But the recording equipment evolved since my first studio session, the mics are not the same. The main change is that I’ve added some “sound sensors” on each strings of my kora, so I can perform in bigger venues. Originally, we played kora for a small audience, with an intimate audience.

Have there been technologies or instruments which have profoundly changed or even questioned the way you make music?

I didn’t profoundly change the way I play kora – except for my technical skills. The main change is about the sound system that evolved over the years, in the places where I tour.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

Collaborations are part of my creative process, it’s a a very natural thing for me. If you don’t converse with others, you can’t free yourself and evolve.

I prefer the human way, I take pleasure in dialoguing with other musicians. You need to learn how to give and how to receive. Music is all about sharing and respect. I value authentic relationships, I don’t like things that are remote-controlled.

Take us through a day in your life, from a possible morning routine through to your work, please. Do you have a fixed schedule? How do music and other aspects of your life feed back into each other - do you separate them or instead try to make them blend seamlessly?

I only have a fixed schedule when I am on tour. Otherwise I always keep my kora beside me, 24/7. I often play all throughout night and stay awake until 4am. So yes, I blend seamlessly my music and other aspects of my life.

Can you talk about a breakthrough work, event or performance in your career? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

It’s not about one breakthrough moment but more about a series of great events or meetings. I’ve developed my career little by little.

It started with my inner circle, the National Instrument Ensemble with its gifted musicians, and then multiple collaborations with kora player Toumani Diabaté, pianist Ludovico Einaudi, my longtime friend and cellist Vincent Segal, the trio 3MA (with Rajery, Driss el Maloumi) and many more.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter into this state more easily?

The ideal state of mind to compose is when I’m relaxed and peaceful. I can easily stay focused on my kora and practice even if there are people talking around me. I don’t have any specific strategies; I’ve improved both concentration and attention while listening to the elders.

Music and sounds can heal, but they can also hurt. Do you personally have experiences with either or both of these? Where do you personally see the biggest need and potential for music as a tool for healing?

For sure, music heals. And this is a relief that I would like to share with others. It gives me energy, hope and the desire to live fully. It helps to free my mind and spirit.

There is a fine line between cultural exchange and appropriation. What are your thoughts on the limits of copying, using cultural signs and symbols and the cultural/social/gender specificity of art?

Cultural exchange requires effort. You need to understand the other culture with respect – some compromises will be necessary. You need to keep an authentic relationship, and listen to others carefully without artifices. You can’t cheat. If it’s forced or appropriated, people will feel it from a healthy distance.

Our sense of hearing shares intriguing connections to other senses. From your experience, what are some of the most inspiring overlaps between different senses - and what do they tell us about the way our senses work?

As I explained before, I’ve learnt to listen before playing kora, to touch with my ears before touching the strings. So yes all our senses are working together. My melodies are also based on my body language and how I pluck the strings of my instrument.

All of my senses are connected when I play kora.

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

In Mali, I came from a family of Nyamakalas (Djelis), the ones that people used to call for conflict mediation and resolution. We are mediators in the Mandinka societies.

Our music plays a role of pacification, so both as a nyamakala and musician I want to appease society. My goal is that my music touches you in your heart and helps you relax. We need to give more space to culture.

What can music express about life and death which words alone may not?

I think that with music you can adapt and be understood by everyone even If you don’t speak the same language. You touch people in a different way.

I often play music for marriages but also for funerals. We accompany the times of celebration and sadness.