Part 1

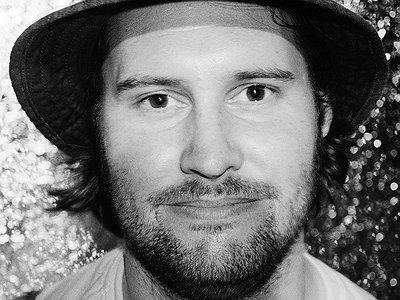

Name: Kyle McCallum (AKA Lumpen Nobleman)

Occupation: Musician/DJ

Nationality: Scottish

Current release: Errors and Remedies EP on Extra Normal Records

Recommendation: Vvpregnat’s Instagram feed is an artwork in itself – you have to see it to believe it / Anja Kirschner’s “part satirical sci-fi, part soap opera and part Brechtian Lehrstueck” Polly II: Plan for a Revolution in Docklands (2006) is a blueprint for the fruitful coming-together of art and politics.

If you enjoyed this interview with Lumpen Nobleman and would like to find out more, visit his website.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What is it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I started making music at the age of ten using Mario Paint for the SNES. For those who aren’t familiar with this idiosyncratic video game’s capacity to facilitate music production, it was basically a case of dragging and dropping classic Mario World icons for example mushrooms, stars and hearts onto a stave and then pressing the play button, with the added bonus of being able to alter the tempo of playback. Each icon made a different sound, and you could stack icons on top of each to make chords or discordant sounds or whatever. I used to record tracks onto video tape off the TV the SNES was plugged into but have no idea if these tapes still exist.

Influences around that time were Kylie Minogue (because she had roughly the same first name as me and she was the only artist whose music videos were available to rent on VHS and the film Local Hero (with its ambient Mark Knopfler soundtrack) which our family came to own after it had been discarded by the post office having not been rented out for over a decade. Incidentally, a less than iconic quote from Local Hero gave my record label, Extra Normal, its name 17 years later in 2010.

The thing that first drew me to music was its roots in communal activity. The record player was the focal point of my grandparents’ house in Aberfeldy. My gran would whistle along to The Migil Five’s version of Mockingbird Hill while us toddlers would twiddle knobs on the stereo cabinet in a Walter Mitty fashion.

For most artists, originality is first preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice? What is the relationship between copying, learning and your own creativity?

My visual art is based around homage, critique, and parody, so copying is a key part of the artform itself rather than being part of a journey towards originality. I see music in a similar way, in that the grand quest for originality can only ever be in vain. For example, where did a seemingly original musical form like House come from? It came from soul, disco, technology, a few other places no doubt and, above all, community. Rather than looking to find my own voice, I prefer to remain in the learning and emulating stage while developing a common voice with those around me.

What were your main compositional- and production-challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

Funnily enough, the main challenges of making music as a child on the SNES in 1993 and producing my first album, Grusha, using Propellerhead software in 2010, were more or less the same. Both Mario Paint and the version of Reason I was using at the time were characterised by their lack of facility for live audio inputs. This meant that, in both cases, tracks were composed by placing icons on a timeline rather than recording instrumental takes in real time. My new Errors EP, on the other hand, was produced by recording and overdubbing keyboard tracks via an audio input, which meant that an element of swing and human error could be injected into the mix, with a view to making the final result more vibrant.

What was your first studio like? How and for what reasons has your set-up evolved over the years and what are currently some of the most important pieces of gear for you?

I have never had a studio and probably never will; I am literally a bedroom producer. My most important piece of gear is the work laptop I held onto after being made redundant from a teaching job last year. Anyone who says that music made using traditional instruments or hardware like modular synths is somehow more valid or objectively better than music made using software can take a running jump. Some of the most exciting music available at the moment was made using cracked software or phone apps by people who couldn’t afford to buy the expensive gear and probably wouldn’t choose to spend their money on a grand piano or Eurorack set-up anyway.

How do you make use of technology? In terms of the feedback mechanism between technology and creativity, what do humans excel at, what do machines excel at?

The theoretically infinite number of tracks available in a digital audio workstation is probably the most meaningful use of technology in my work. This is not always a positive factor, as sometimes it seems easier to produce something coherent while working within certain limits, on the whole though, I think the possibilities offered by digital technology far outweigh the drawbacks.

To answer the more philosophical part of your question (and to paraphrase Cesar A. Cruz) humans excel at providing comfort by giving the music the aforementioned swing and introducing the relatability of human error, while machines revel in producing sounds that disturb humans. When members of the public first heard the effects produced at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop in the early ’60s for programmes like Doctor Who, they were genuinely frightened by them as they simply couldn’t fathom where these otherworldly sounds were coming from.

Production tools, from instruments to complex software environments, contribute to the compositional process. How does this manifest itself in your work? Can you describe the co-authorship between yourself and your tools?

Each of the four ‘Errors’ on the new EP began life as a pre-set keyboard drum rhythm. The rhythms’ low pass filter cut-off, resonance, envelope generator intensity/release, arpeggio gate/velocity/length and tempo were then edited digitally in real time via the scientific procedure known as knob-twiddling. Ultimately, the beat that forms the backbone of ‘Error I’ rematerialized as an undefinable polyrhythmic affair, while ‘Error II’ came out the other side of this compositional process sounding uncannily like the classic Amen break synonymous with Jungle.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

My friends and I have been file-sharing since the MP3 became ubiquitous in the early 2000s. Before this, my school friends, Liam and Joe, would make me mixtapes in the late ’90s, including tunes by The Beta Band, Lemon Jelly and other left-of-centre acts of the time. While these kind gestures would ultimately inspire me to develop my own musical taste, I never saw fit to give them mixes in exchange, as all I had to offer was The Beatles and The Mama and the Papas. As great as those bands were, they were merely a reflection of what happened to be stuck in my parents’ malfunctioning car tape deck at the time, as I simply had no taste at this stage.

I started to develop my own taste at art school in Dundee between 2001 and 2005 by attending club nights like Soul Cellar at Sessions Lounge and Do This Do That, a house music night at the student union. The moment that really set me on a path of musical discovery was when I bought Soul Jazz Records’ New York Noise: Dance Music from The New York Underground 1978-1982 from HMV in Edinburgh in 2003. While the double LP was full of raw disco punk such as ‘Can’t Be Funky’ by Bush Tetras that I related to instantly, it also contained some fairly harsh no wave that was too ripe for me at the time but would inspire me for years to come.

In 2011, I started the Extra Normal Mix Series as a way of broadening my musical horizons further. There are 100 mixes in the series, including several guests’ contributions from the likes of Jennifer Lucy Allan from Arc Light Editions and Fielding Hope of Café OTO.