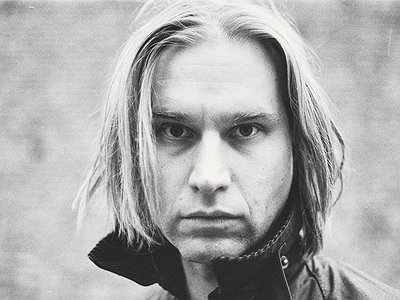

Name: Martyn Heyne

Nationality: German

Occupation: Composer, guitarist

Current release: Martyn Heyne's Eight Reflections in Darkness is out via Tonal Institute.

Recommendations: Book: Werner Herzog - Every Man for Himself and God Against All – Hanser; Painting: Catherine Lampert (editor) - Frank Auerbach – Tate; Music: Rossburger Report - 2 - Strange Ways Records

If you enjoyed this Martyn Heyne interview and would like to know more about his music, visit his official website. He is also on Instagram, and twitter.

For the thoughts of some of his collaborators, visit our Ben Lukas Boysen interview and our Nils Frahm interview.

When I listen to music, I see shapes, objects and colours. What happens in your body when you're listening?

Like you, I can be a little synaesthetic about sound and colours, but mostly when I listen to music I try to concentrate. The better I can concentrate, the stronger the experience is.

I recorded some incredible pieces of music when I had almost no idea what I was doing. What were your very first steps in music like - and how do you rate the gains made through experience and knowledge that followed?

Some of my first ‘compositions’, or rather little things that I would play as a young child, funnily were much more geometric, as in based on the shape of the keyboard, rather than on functional harmony. Sometimes outright dissonant - I just did not hear it that way yet.

Experience and knowledge are of course essential, and they also have the inherent danger that one does something automatically, or routinely, which is poison for music.

It is generally believed that we make our deepest and most incisive musical experiences between 13-16. Tell me what music meant to you at that age, please. Is music is still able to move you as strongly today?

While at 15 I wanted to drop out of school in order to do music full time. I feel like it has only become more important and meaningful to me as I get older.

It is true that the experiences at that age tend to remain relevant to us, but there is always so much more to discover! The music I knew back then is just a small fraction in the pie chart of what I love now.

What, would you say, are the key ideas behind your approach to music and what motivates you to create?

I have come to think of it as some kind of disease that I am not making any effort to cure.

Paul Simon has been quoted as claiming that “the way that I listen to my own records is not for the chords or the lyrics - my first impression is of the overall sound.” What's your own take on that and how would you define your personal sound?

Sound, as in the tone and style rather than the harmonic relationship, is so important today because the element of fashion is the biggest driving force in the recorded music situation of today.

When I see industry professionals check something out, they tend to skip through it very quickly, listening to 5 seconds here and 5 seconds there. What you can hear with such a system is the style and fashion, but you cannot detect a musical narrative. And so, quite often there is none.

Don’t get me wrong, I am obsessed with sound! But it is just the candy. The content is why music is more nurturing than sweets.

Sound, song, and rhythm are all around us, from animal noises to forces of nature. What, if any, are some of the most moving experiences you've had with these non-human-made sounds? In how far would you describe them as “musical”?

I would not call natural sounds music in the same way that I do not want to call everything art. If one expands these words endlessly they lose their meaning.

Music is necessarily made by a human because it functions when it becomes, within the framework of music, something that relates to the humanity of another person - the listener - and rings true. Intention is a necessary ingredient. Even musicians that work with elements of chance use these to be presented with options, but then choose from those options with deliberation.

So, natural sounds can be wonderful and interesting but they are not music. You can even turn it around: the rain, the wind, the waves, birds etc. are all sounds that can be continuous and even loud, but they will not generally become annoying, or ugly.

The constant bombardment with musical sound however - phone ringtones, radio in taxis and restaurants, boom boxes in the park etc - is annoying and a pollution issue, if I may say so. It is the intentionality that transforms it for better or for worse.

From very deep/high/loud/quiet sounds to very long/short/simple/complex compositions - are there extremes in music you feel drawn to and what response do they elicit?

I like it all, it just has different strengths.

A very soft solo performer will have more detail and a light, and silvery quality to the sound, that gets covered up when you start adding more elements. But then you have, well, more!

Loud is obviously very powerful, too. I have seen performances that were nothing but loud. It will not fail to have an impact. It does however give you nothing to take home afterwards, except perhaps a ringing set of ears.

From symphonies and traditional verse/chorus-songs to techno tracks and free jazz, there are myriads of ways to structure a piece of music. Which approaches work best for you – and why?

Personally I work more bottom up than top down. That means I start and see where it can go. I try options: no, no, no, no, yes, here. And continue. Sometimes, when I am most of the way there, I make global adjustments or move bits around in order to improve the overall structure.

But I do not generally start by setting a frame and then filling it in. It also depends on the instrumentation and scope of the piece.

Science and art have both obvious overlaps and similarities. Do you conduct “experiments” as part of making music and do you make use of scientific insights for your work?

Perhaps my own experiments are more aptly described as ‘happily messing around’ but I will incorporate scientific insight from others.

For example, the economist and psychologist Daniel Kahnemann has written the great book Thinking Fast and Slow which has the best explanation of practicing that I have come across. In his terminology, practicing simply means moving things from slow thinking to fast thinking. Even though the book is about other things as well, and does not directly talk about musical practicing, I really recommend it for musicians.

Ironically the book has a few bits about actual music and, please excuse me, those are utterly wrong.

Do you think "objectivity", “quality”, and “truth” have a place in art or is it all a question of taste?

I would say objectivity and quality are no matter and truth is everything. If it is not true, it’s pretentious, and it cannot enrich the recipient.

But I do not mean true in a fact-checking type of way. I mean that if you see /hear / feel it you go: “Yes! That’s how it is”.

By now it has been well established that visual and acoustic elements can complement each other. Do you see points of contact between hearing/ listening and the other senses as well?

Perhaps, but my preoccupation is with listening.

Does the way you make music reflect on the way you live your life? And vice versa, can we learn lessons about life by understanding music on a deeper level?

Yes, we absolutely can learn lessons about life from music. Concretely, music pushes us to connect the emotional and the cerebral, which is potentially the most important ability for children and young adults to develop. For me, the first area where it shows if I am neglecting my mental or physical well-being, is in my playing.

And beyond that, the way music resonates with you always tells you something about yourself, that you would not have known otherwise. That’s also a lesson about life. Your very own life.

Do you feel as though writing or performing a piece of music is inherently different from something like making a great cup of coffee? What do you express through music that you couldn't or wouldn't in more 'mundane' tasks?

Yes, it seems to me that a cup of coffee and music are completely different. There is a level of craftsmanship involved in both, but that is the end of the cup of coffee and only the beginning of music.

Every time I listen to "Albedo 0.39" by Vangelis, I choke up. But the lyrics are made up of nothing but numbers and values. Conversely, many love songs leave me cold. Can you help me understand this and why the same piece of music is capable of conjuring such vastly different responses in different listeners?

There are two caveats here: Firstly, in addition to numbers, the lyrics also include words that relate to the solar system and space in general. Humans have forever looked up at the stars in amazement, and the recent photos of the James Webb telescope are very moving. Are you perhaps having an emotional reaction to the apparent smallness and fortuity of our existence?

Secondly, this is not only a piece of music but - just like every song with lyrics - technically an interdisciplinary piece of work because it is music combined with poetry. The distinction is often overlooked, because this particular mix has become more common than music - or poetry - alone. It matters because the characteristics of both come into play. Would you choke up if the spoken word was in a language you couldn’t understand? If not, the issue may not be on the musical side so much as on the poetic.

Finally, let’s get to the music. Yes! It’s absolutely possible and happening all the time that the same music will be considered comical by one listener, and tragic by another. Oppressive for some, yet exhilarating for others etc. Music is multi-faceted emotionally, and often combines different feelings, and even other things such as thoughts, or simply perceived realities - emotional or not - that just ‘are’.

For example, if you are stood in front of a huge mountain, is that a happy feeling? Or sad, or intimidating, or liberating? It depends on the person and the context, doesn’t it? All you can say is that, for most people, the experience wouldn’t leave them entirely cold.

Music is not about concrete things but real things and true things nonetheless. If music were a tree we could have the tree instead, but because music is about reality and truth within the world of music, there is no substitute.

If you could make a wish for the future – what are developments in music you would like to see and hear?

It’s a great moment to ask me about my wish for the future of music because a few years ago I may not have had one. Now, in light of the seismic shifts that musical life has endured as a result of our reaction to Covid, I would like to tell you about a film I have seen recently:

It had some old black and white footage about the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra. Back in 1948, West Berlin was cut off from the western world and could only get supplies such as food, and meds via the Berlin Airlift, which was basically a string of cargo planes in the sky. A tremendous effort of a quarter of a million flights over a period of 11 months to keep the city alive. Actual dire times and scarcity! Yet the orchestra, including their instruments, was flown via the airlift, to England for a tour. That’s the value that people attached to it!

My wish for the future is that we not only think of what is essential today, but also about what is essential this month, this year, and beyond because some of that will also have to happen today.