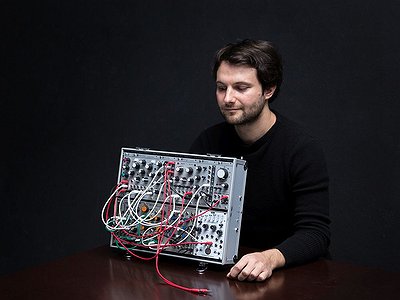

Name: Matthias Puech

Occupation: Composer, designer, software and instrument developer, researcher,

Nationality: French

Current Release: Matthias Puech's A Geography of Absence is out via NAHAL.

Recommendations: The solo piano works of Chris Abrahams; the naïve erotic paintings of Arrington de Dionyso.

If you enjoyed this interview with Matthias Puech and would like to stay up to date on his music and creative activities, visit his official website. Or drop by his profiles on Instagram, twitter, and Soundcloud.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I started “composing” music in my early teens, as a kind of game and a way to explore the world around me.

I had just discovered pop music, which I guess for most teenagers is a major event and a source of liberation. As with many other topics for me the fundamental question was “how is it made?”. I had just quit piano lessons at the conservatory after a few years of struggling with the rigor and the lack of creativity; classical music practice felt more like an athletic discipline than a form of art.

There was something about sound and music that struck me very early, contrary to other forms of creation: its intangible and ephemeral nature, the fact that it is lived only in the present, that it is so physically a manifestation of time, and yet its unquestionable emotional immediacy.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

When I started practicing electronic music, I spent a lot of time recreating works that I liked, as a kind of technical challenge and retrospectively to, by contrast, make my own voice emerge. I learned a lot about sound design and composition this way, and also which directions I did not want to explore myself. Progressively my copyist work mutated, by little successive steps: trying to replicate a piece that I liked, I would veer in a different direction, eventually ending up in a place that had nothing to do with the original. Sometimes, unexpectedly, I was ending up with a result that I could enjoy myself as a listener, and yet had not heard before.

I still work a bit in this way sometimes: a piece, an album, or a way of working that I hear in others triggers my curiosity and makes me ask myself “how is it made?”. I still go to shows as often as I can, and often find inspiration there, in the dark concert halls; these are moments of half-passive daydreaming that I cherish, and I know to be fertile: there is something so unique in this discovery that no two pairs of ears, hands and abilities will produce identical results.

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your creativity?

I don’t really see how it would, to be honest, as much as I don’t quite know how to define my identity. Anyone and no one could do what I do, really.

What were your main creative challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

Like many others I struggled at the beginning to get from sounds to message. This is really what composing means: taking a set of sound entities, be it individual parts or static “moments”, and making them coexist to deliver something to the listener, tell them a story.

Of course, I never solved this difficulty, and it is still a recurring question, but it has gotten easier and easier because I feel like I can envision the story I want to tell earlier and earlier in the composition process, which is consequently less and less a trial-and-error process.

As creative goals and technical abilities change, so does the need for different tools of expression, be it instruments, software tools or recording equipment. Can you describe this path for you, starting from your first studio/first instrument? What motivated some of the choices you made in terms of instruments/tools/equipment over the years?

I began making music with a simple computer running (Emagic) Logic, a few plugins and a microphone. A lot of my experiments had to do with satisfying my curiosity on sound, which made me rapidly delve into more principled tools like Max/MSP, which I had discovered at IRCAM. For many years this was enough for me, but always kept me longing for a more direct, intuitive and at the same time more primitive instrument.

My music output really got serious only at the point when I started developing my own instruments. I was using modular synths but was frustrated by some aspects of the modules I was buying off the shelf, and I was daydreaming about making my own, just to fulfil my own musical needs. So I quickly started hacking into existing modules (hacks that I released as the Parasites project, which still enjoys rather wide use to this day), and then started working with the American brand 4ms Company, who released my own designs.

Have there been technologies or instruments which have profoundly changed or even questioned the way you make music?

I discovered modular synthesizers right before the boom of Eurorack, and it was a turning point for me. Having been exposed to the modular nature of tools like Max/MSP on the computer before, I was in quite familiar territory, nonetheless it was a revolution in my day-to-day practice. It was primal, playful, it spoke my language of maths, physics and signals, and it offered more than a blank canvas when starting off; I fell in love with this instrument.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

Except for a few fun but not properly fruitful attempts I have never really collaborated with another artist unfortunately. I think it comes down more to my own difficulty to make concessions and to accept someone else in this rather private place of mine, than to a lack of opportunities. But I am working on it!

Take us through a day in your life, from a possible morning routine through to your work, please. Do you have a fixed schedule? How do music and other aspects of your life feed back into each other - do you separate them or instead try to make them blend seamlessly?

These days most of my schedule is filled with my job at GRM, where I am a research scientist and a software developer, and taking care of my young kids. The moments I can dedicate to music are scarce and irregular so I have to make the most out of them.

Some of this time is spent playfully interacting with the modular synth, with no real concept or goal in mind, but the bulk of it is spent on the computer, composing and arranging mostly already-recorded sounds. And some rare and precious music moments also happen in silence, in public transportations or in concerts, when I can let my thoughts drift and imagine a piece, a patch, a process …

Can you talk about a breakthrough work, event or performance in your career? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

There was a defining moment when I understood what I wanted to bring to the world musically.

I was just beginning to fool around with a small Eurorack rig and had recorded a few patches in a small sound library, just for memory. Almost by accident, I layered two recordings on top of each other, and listened in awe: the two parts, generative patches that evolved slowly on their own, with no intervention from me, were interacting, almost dialoguing with each other as if there was an intent.

At this point I understood that this dialogue was not happening in the machine or in my planning ahead, but only in the listener’s ears (my ears at that time). This when I realized what my own voice could be: discover music that emerges almost by itself.

This piece, “Make or Break”, was later released on my debut EP “Threshold”.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter into this state more easily?

Electronic music has this specificity that it can be decorrelated from an interpretor’s gesture. The responsibility is therefore shifted from practicing the gestures to practicing our listening ability. As an electronic musician, we should therefore always be attentive to this fleeting moment when sound becomes music, and this acute listening state is I think what we are chasing.

We are listeners of our own music as much as we are actors of it, and that’s an art that can be practiced and trained. Listen to everything, music, pleasing or displeasing sounds, accidents… being open to the emergence of a music, not as an activity with a dedicated, limited span of time but everywhere, anytime.

This is the state of mind I am constantly seeking for.

Music and sounds can heal, but they can also hurt. Do you personally have experiences with either or both of these? Where do you personally see the biggest need and potential for music as a tool for healing?

My two latest albums revolve precisely around this idea of processing grief, in two very different ways. I lived through quite rough times in my personal life, and making music had a crucial role in living through them; I sometimes even ask myself if it is not the very reason I have been composing in the past 5 years.

Alpestres (2018, Hands in the Dark) was imagined as an escape into a fantasy space, one of childhood memories and simple nostalgia for when life was so much simpler and candid. A Geography of Absence (2021, NAHAL recordings) is on the contrary embracing pain and grief in a much more direct way; I was specifically searching for sounds that would hurt, almost as a cathartic experience.

But this is only my own viewpoint; from experience I know that listeners receive the music in very different ways than I hear it myself, and that’s a good thing: once music is released, it belongs to the listeners, not to the composers!

There is a fine line between cultural exchange and appropriation. What are your thoughts on the limits of copying, using cultural signs and symbols and the cultural/social/gender specificity of art?

I am sorry, but I really don’t have anything meaningful to say about this. It’s just not a question I have asked myself (enough?).

Our sense of hearing shares intriguing connections to other senses. From your experience, what are some of the most inspiring overlaps between different senses - and what do they tell us about the way our senses work?

Hmm, good question ... but I don’t believe I am personally wired with these kinds of synesthetic connections. If there are some, they are often linked to common preconceptions (hot/cold, cozy/uncomfortable), to the visualization of sound through the studio’s tools (colors, space), or to musical notation (width, height). But I am curious to read other people’s answer to this one!

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

As many in my generation I am very conscious about environmental issues, especially the massive extinction of natural diversity we are witnessing. One of the ways this was first realized was through comparisons of recordings of natural habitats (see Bernie Krause), and audio and music are also I believe a powerful tool to help raise even more awareness on the matter.

A lot of my work revolves around creating these artificial ecosystems of sounds which interact in complex ways with one another; the delicate balance of sounds functioning as an allegory of the delicate balance of life.

What can music express about life and death which words alone may not?

Music is invisible; it is the art of the passing of time. I believe that it provides a direct access to our emotions, unfiltered by the load of language or space.