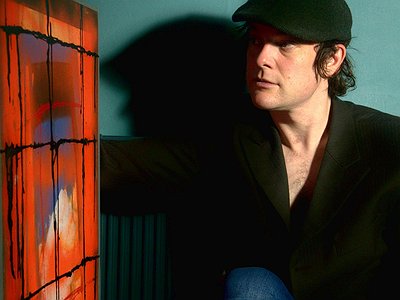

Name: Nick Hudson / The Academy of Sun

Nationality: British

Occupation: Composer

Current release: Nick Hudson's Font of Human Fractures is available via The Academy of Sun's bandcamp account.

Recommendations: Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia (1983) - I visited the Tuscany locations where he filmed this beautiful work and walked in the thermal hot springs where Catherine of Siena passed on her path to sainthood. I also visited the roofless abbey of San Galgano which dominates the astonishing closing shot.

Otherwise, Anselm Kiefer’s combined body of work - he’s one of the few artists who both fills me with awe whilst dredging from me tears from the deepest well of my soul.

If you enjoyed this interview with Nick Hudson / The Academy of Sun and would like to know more, he is on Facebook and Soundcloud.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I played piano from six years of age but never united music and words until I was around twenty-one when it felt it had become a necessity. Prior to that I'd long-since fallen in love with sound itself as a malleable material and was intensely beguiled by pitch-shifting, reversing, changing the speed and essentially breaking sound through distortion, counter-intuitive EQ-ing and pushing it to horrible corrosive frequencies that would make me the nemesis of bats and alsatians alike. This aggressive experimentalism remains but now hangs in vapour around formal composition rather than being the sole content.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as an artist and the transition towards your own voice?

I fully concur. When I began singing I would strive to emulate vocalists I admired and from these genuflective pantomimes would seize fragments of technique and colour via which to collage my own voice. This stands true compositionally as well as vocally.

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your creativity?

Comprehensively. Likewise the rare and fleeting moments when the walls of its perceived form become somewhat blurred, indistinct and dis-associative. Likewise though I fluctuate between increments of autobiography and fabulism, but even the latter of course is a crucible for projected autobiography and the reflections of lived experience.

What were your main creative challenges in the beginning and how have they changed over time?

I'm self-taught as a producer so there was a vast period of trial and error (and sometimes the error birthed techniques I use to this day). It took more tech-savvy friends to introduce me to the notion of interfaces and basic EQ-ing.

My first record was tracked entirely on an SM58, even the harps and violins. (But hey, if it's good enough for Julian Cope - he loved that record.) That said I'm proud of the singular tonal and formal character that has (hopefully) emerged from my brash and thrashing autodidactism. I self-produced entirely up until seven years ago, only entering a professional recording studio to track a record in 2016. I've of course never looked back.

The other challenge of course is money, and that remains so today. But of course restrictions can be emancipating creatively. I just could do with less of them!

As creative goals and technical abilities change, so does the need for different tools of expression, be it instruments, software tools or recording equipment. Can you describe this path for you, starting from your first studio/first instrument? What motivated some of the choices you made in terms of instruments/tools/equipment over the years?

First it was Audacity, which generously allowed for the explorations into the malleability of sound as expressed above. Then it moved into Cubase and now I use a combination of that and Ableton and have been exploring MIDI more recently courtesy of the latter. Instrument-wise I trained in piano from six, added guitar at thirteen and voice at twenty-one. I've since jettisoned guitar as all but a compositional tool and have been focusing intensely on the voice.

The real coup for me in terms of tech was when a dear friend gave me a Neumann U89 condenser mic which opened up such an expanse of frequency capture to me and thus saw me studying productions techniques with a little less cavalier an approach out of respect for the pedigree of the microphone.

Have there been technologies or instruments which have profoundly changed or even questioned the way you make music?

I once bowed polystyrene and a clothes horse and bruised my knuckles to bloodied stumps pummelling a stairwell banister in an attempt to become Tom Waits when I was twenty-one. I discovered the Soviet ANS photo-optic synthesizer via Tarkovsky's Stalker and Coil's record of the same name and it has enchanted me ever since. I have negotiated with the Glinka Museum in Moscow to access and use the synth, but communication is currently paused on that matter. I have a fondness for synth apps on my iphone. When my band played with Damo Suzuki I used a Gyrosynth that acts like a Russian numbers station and a theremin had an irradiated baby. Obviously formal propositions from the likes of John Cage and Erik Satie propelled me into self-interrogation as to my motivations and attitudes surrounding making music and art in general.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives through, for example, file sharing, jamming or just talking about ideas?

I talk a lot with Toby Driver of Kayo Dot about composition and atmosphere and the emotional aspect of artistry in general. Toby and I also made a duo record in NYC in 2020 of which I'm enormously proud.

Otherwise I have tended to be a fairly auteur-ish writer until very recently: the song would be finished while allowing for a strong cast of musicians to lend their own colour and character arrangementally. Recently I actually embarked on my first co-writing engagement with a beautiful artist called Oli Spleen which saw me compose and produce the music to his lyrics and melodies. That was in many ways revelatory and I'm now open to more such joint ventures. I tend to converse more with novelists and painters than I do with musicians.

Take us through a day in your life, from a possible morning routine through to your work, please. Do you have a fixed schedule? How do music and other aspects of your life feed back into each other - do you separate them or instead try to make them blend seamlessly?

I have tended to avoid routine for all of my adult life, very deliberately. I’m intensely restless and hyperactive, with a low boredom threshold. I find breakfast troublesome so I tend to cook a full hot meal rather than funnel tepid cereal down my throat. Quadruple espresso usually gets me oriented. Then I’ll do emails. My work network is global so I (happily) find myself doing correspondence at crazy times of the day, across various time zones. Fortunately I’m an insomniac which makes this pretty amenable.

I have music running through my head constantly. Despite that, there are vast hiatuses between periods of composing as I increasingly focus on other media - prose and painting. I’ve written over a thousand songs and I’m negotiating various new currents in my life and don’t feel any urgency to compose new music right now.

Can you talk about a breakthrough work, event or performance in your career? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

Letters To The Dead (2011) felt like a breakthrough in that it was the first to feature a tonne of orchestral instruments, significant guest appearances from various members of Kayo Dot, and it was the first time I’d recorded components in St Mary’s Church in Brighton, with whom I at this point have enjoyed a long history of recording and performance. Letters was the first record, in summary, to enjoy the nourishment of air, liberated from a closed system of hardware and software. It was also my first vinyl release - and a short feature film. It is an abstract narrative work and formally bleeds into neo-classical realms.

Other key moments include supporting Mogwai at Brighton’s 3000-capacity Dome venue in 2018, and doing my first full tour of Europe and the middle-east with Toby Driver in 2016.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter into this state more easily?

I couldn’t comment on an ideal state of mind as I essentially I cannot turn it off, at least in terms of the actual generating of ideas.

As for the disciplined refinement and execution of them, well that’s more editorial. The ideal headspace for that is solitude, coffee and having the smartphone turned off. I’m increasingly minded to throw away my iPhone and get a rudimentary burner phone and delete all of my social media profiles and accounts. Dreams provide a lot of material, as does traveling - motion seems to tease forth ideas. When I was writing my novel in Sofia last October I forced myself into a discipline of 2000 words a day, irrespective of headspace, hangover or lazy reluctance. Invariably I’d find myself accessing the required headspace after a few hundred words.

Music and sounds can heal, but they can also hurt. Do you personally have experiences with either or both of these? Where do you personally see the biggest need and potential for music as a tool for healing?

Music is air moving at various rates around us, like a tapestry or a noose. It can lend the gift of flight and invoke angels or it can induce claustrophobia and terror, the latter of which releases adrenaline, and is thus a useful exercise. It can be a love letter or a bullet. I prefer to work in the realm where it heals - both in my lyrics and in my harmonic and sonic choices.

There are Tuvan shamans and artists such as Meredith Monk and Tanya Tagaq in whose work I see and feel a great wealth of healing and cathartic energy. I have phenomenal respect for these kinds of figures and aspire to humbly join their ranks as I move along the path.

There is a fine line between cultural exchange and appropriation. What are your thoughts on the limits of copying, using cultural signs and symbols and the cultural/social/gender specificity of art?

I won’t be getting dreadlocks any time soon. But if I were to draw on Klezmer harmony it would be out of a respectful love of the emotions it unleashes and the endorphins that they release in accompaniment. I think Madonna demonstrates very ably and repeatedly lines crossed in terms of cultural appropriation. She’s an ambassador for the most wrecking-ball way of doing it.

Our sense of hearing shares intriguing connections to other senses. From your experience, what are some of the most inspiring overlaps between different senses - and what do they tell us about the way our senses work?

I’m fairly synaesthetic anyway so I don’t distinguish hugely between art forms. I think the reason I move between them is because I become restless with the various technologies involved and am inclined to mix them up. I very often see sound as abstract three-dimensional visual forms.

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

It’s all I know. It embodies my politics, my emotions, my life narratives, my resistances to mainstream modes of being; it’s my protest and my comfort and my infant and my guardian. If I didn’t have it I suspect I would have been sectioned a long time ago.

When I receive feedback whereby a certain song, painting or poem has resonated deeply with someone, it’s the most enriching feeling, and helps remind me why I do it.

What can music express about life and death which words alone may not?

Universality. And it offers a connectivity beyond the borders of spoken and written language. Also music has an afterlife, in the mind and the heart. In terms of life, at its most transcendent it can remind us of the vast potential for beauty and articulation of the sacred that humans possess when they’re not engaging in disaster capitalism or more direct forms of murder.