Part 1

Name: Steven Jones

Nationality: American

Occupation: artist/writer

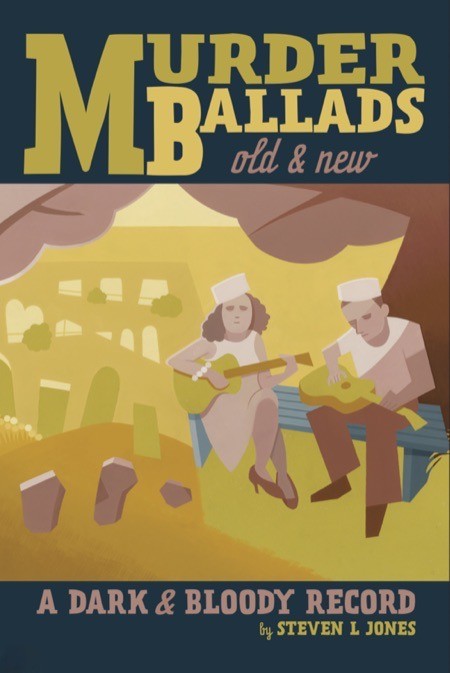

Current Release: Murder Ballads Old and New: A Dark and Bloody Record with Feral House

Recommendations: Glenn Gould’s second recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, recorded before he died in 1982. Gould’s youthful first recording (in 1956) is a technical tour-de-force, but his middle-aged follow-up is far more expressive—reflective, autumnal, and elegiac / Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music, first released in 1952, remains a life-changing listen—a mammoth set of hillbilly, blues, gospel, Cajun, cowboy, etc., tunes from the late ‘20s and early ‘30s, curated by a bohemian oddball who arranged them according to arcane schemas with a poet’s instincts.

If you enjoyed this interview with Steven Jones, visit his website to see his artwork and read reviews.

When did you start writing about music - and what or who were your early passions and influences? What was it about music and/or sound that drew you to it?

I was a weird kid. I started reading film and music criticism in grade school. This was during the pre-Internet heyday of the capsule review and long-form essay. I learned a basic critical vocabulary and the importance of historical context from books and magazines. I wrote my first music reviews for the high school paper, panning a Van Halen album and championing new wave bands, neither of which endeared me to the stoners or the keg party crowd.

I was immersed in music before I could speak. My mother was a violinist, my father was a choir director, and I spent my pre-verbal years hearing Bach and a cappella choral music as well as pop, country, and rock. Consequently, music affects me more deeply than anything. Rock and roll was my youthful passion, but I was always stylistically curious and open to new sounds.

For most artists, originality is preceded by a phase of learning and, often, emulating others. What was this like for you: How would you describe your own development as a writer and the transition towards your own style?

I always read voraciously about the subjects I loved. My first published essays and reviews were in art magazines, and they aped my early influences—rock mag writers like Lester Bangs and Greil Marcus, film critics like Dave Kehr and Jonathan Rosenbaum, and art critics like Donald Kuspit and Robert Hughes. I was also a visual artist, and over time, I realized what all good creators do: that personal vision and voice trump innovation and theory. So, I gradually jettisoned everything in my work that wasn’t mine. Critical to this process was Lester Bangs’ advice to writers (which I mentally reference to this day): “Just be yourself. Be penetrating. And don’t fuck around.”

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your work?

For me, they’re inseparable. All my work is an extension of my outlook and experiences—more obviously in my art, but also in my writing. While it’s true that I rein in the personal in critical mode, the resulting “objectivity” is largely illusory. At my most neutral, I’m still working from my gut, life, insights, and transformations.

What were your main challenges as a writer when starting out and how have they changed over time?

I’m gloriously impractical with little head for business. So, most of my challenges were real-world in nature. I lack the self-promotion gene, and branding and career coaching make me queasy. But I force myself to engage with these facets of my vocation as best as I can. I’m a diligent, hard worker, but one thing I learned long ago is to get help, both casual and professional, from people who have the skills I lack.

How do you see the role of music journalism in the creative process? Should it amplify public taste, distinguish the good from the bad, inform, promote artists, or, as Howard Mandel put it, “illuminate, educate and entertain” readers?

Different writers do all of the above, and there’s room for each method. Peter Guralnick said he started writing about music not to provide people with a consumer guide or to trash artists he didn’t like but to share his enthusiasm for what moved him. My ethos is similar. I often write stuff that’s been swimming in my head for weeks, months, or years—thoughts about music, how it sounds, and what it means, that I feel compelled to codify in language and share with fellow enthusiasts. I don’t avoid negative criticism, but I’m not animated by snark.

Whom do you feel your obligation to – the artists, the readers, the publication you're writing for?

I always start with myself—focusing on capturing my vision in my voice. But I listen and re-listen to the artist throughout the process, double-checking my impressions, and refine the text for the reader to ensure it’s clear and understandable. As for the publication, I feel obliged to follow their format and be consonant with their sensibility. But I’m strident about my vision and voice.

I once reviewed an art show for a local paper and skipped over a workaday Warhol print to highlight other artists. My editor told me that the Warhol would be the featured photo and insisted I add text about the piece to my review. I had nothing to say about it, and we argued. Finally, I found a way to mention the Warhol in passing before returning to the works that engaged me. But the pressure to refocus the piece according to a photograph (and highlight a world-famous artist who hardly needed the publicity) irked me.

Collaborations can take on many forms. What role do they play in your approach and what are your preferred ways of engaging with other creatives, writers and possibly even the artists you're interviewing or working with for a piece?

I’ve collaborated with artists, musicians, filmmakers, and my students on projects, but my writing is pretty much a solo act. An exception was a musical launch for my book Murder Ballads Old & New: A Dark & Bloody Record, wherein musicians interpreted songs from the text in various styles and formats. I helped organize the event and read short excerpts between performers; otherwise, I let them do their thing. I work with editors and gallerists, but more direct collaboration is now rare for me—something I mostly did when I was younger.