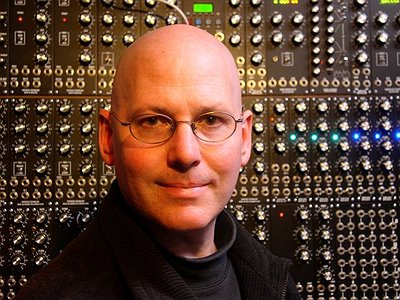

Attracted by energy

Robert Rich wasn't just there, when ambient happened. He made it happen. When Rich and Steve Roach, in one of the great coincidences of musical history, released their debut albums in exactly the same year, the genre was little more than an avantgarde idea first proposed by Eric Satie and later popularised by Brian Eno. Instead of merely fine-tuning the formula, Rich saw it as a point of departure for something deeper, a music more vast, mysterious and meaningful than anyone could ever have imagined when Music for Airports was released in 1978. Ambient, in his hands, was a tool capable of uncovering the hidden connections between the conscious and the unconscious, of re-uniting the realms of dreaming and waking, of breaking into expansive spaces through the fabric of the abstract. Rich's much-publicised sleeping music concerts were merely the tip of the iceberg of an oeuve constantly seeking new modes and forms of expression. Fom seven-hour albums to iphone apps this genre has kept growing, transforming and mutating in inspiring ways for more than thirty years. If ambient has a future, and everything seems to suggest it does, then Rich's influence on it will undoubtedly remain as big as his impact on its past.

When did you start writing/producing music - and what or who were your early passions and influences?

When rather young, I sang in a choir and tried to learn viola for a few months, but something about written music didn’t work in my brain. Maybe around 12 years old I started improvising on my parent’s piano, and a year later started building cheap synthesizer modules from kits. That was around 1976. At the time I had discovered the European space music scene and I wanted to sound like Klaus Schulze, or maybe like Keith Jarrett. I just wanted to move my hands and hear music come out. My father played jazz guitar – cool jazz like Barney Kessel or Stan Getz – and also loved Bach and Handel, so we had good music around the house.

I think, as my tastes developed from those early days, two radio stations in my area played a big role in shaping my interests. A college station, KFJC, became one of the first in the USA to play punk, industrial and experimental rock around 1977. Also, the listener-sponsored station KPFA had a music director Charles Amirkhanian, who was closely connected to the new movement of tonal avant-garde. On KPFA I heard Terry Riley, Lou Harrison, Harry Partch, John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Annea Lockwood, Maryanne Amacher. At the time, the music scene in San Francisco was alive with underground activity: The Residents, Tuxedomoon, visits from Cabaret Voltaire and Throbbing Gristle. I found myself more attracted to the pure energy of sound, not so much to the structures of musical harmony. The industrial/punk aesthetic inspired people to create art just because they had something to say. That was a huge inspiration, even though I became known for a more quiet sort of language.

What do you personally consider to be the incisive moments in your artistic work and/or career?

Several discoveries shaped my lifetime direction I think. First was learning about just intonation, which is a way to think about tunings on the basis of ratios, so that chords relate to the harmonic series. Hearing Harry Partch and Terry Riley shaped the sound of my music very strongly.

Then, as I started thinking about using music in more subtle psychological ways, with awareness of slow time scale and trance, this connected many of the disparate influences and led to the idea of all-night sleep concerts. Throughout traditional societies, from Indonesian Wayang to Navaho medicine ceremonies, all-night concerts of Indian classical music, Fluxus performance art, and psychedelic happenings from the Sixties – these all shared a common element that attracted me to a certain energy in music, so the sleep concerts were an attempt to synthesize a new type of trancelike experience with music, that fit my love for environmental sounds and the honing of sensory attention.

What are currently your main compositional- and production-challenges?

It’s difficult to put into words, but my biggest challenge remains to communicate my awe at being alive. My attempts to express this in sound always seem to fall short. For this and other reasons, I struggle to remain interested in the music I create. I still have many ideas and unrealized projects, and I still love music in general as a medium for communication; but I feel inadequate in my own ability to eff the ineffable.

What do you usually start with when working on a new piece?

Hopefully a new idea starts to bubble up from a hidden place inside, but often I find myself stumbling around trying to listen for that whisper. Occasionally, I will use improvisational methods to help ideas to start flowing, or play little surrealist games with permutations of ideas - and then the process of filtering good ideas from dumb ones helps to solidify a direction. Other times the music just starts itself and I can hardly remember what I did by the time it’s finished.

How strictly do you separate improvising and composing?

They coexist all the time. Often for me, the compositional process consists mostly of meticulous editing as I try to shape improvisation into a coherent form. However, usually a piece starts with core ideas that involve tunings, rhythms, numerical relationships, or a landscape of sound that I am trying to uncover. In that sense, the improvisation takes place as I seek to express the landscape that lives in imagination, which you could say is a compositional guidepost.

How do you see the relationship between sound, space and composition?

Ideally, the music would involve the listener so completely that it merges the exterior world of sound and spatial localization, with the listener’s own interior world of imagination and wonder. I am strongly attracted to the idea of seamlessness in art, blurring the lines that delineate intention from pure form. So in this sense my music may seem less conceptual or intellectual, and perhaps more visceral and sensual. Ideally, as the sensual elements unfold themselves in some spontaneous experience within the listener, they help to blur the perceptual boundaries between internal and external.

Do you feel it important that an audience is able to deduct the processes and ideas behind a work purely on the basis of the music? If so, how do you make them transparent?

Once again, I think the idea of seamlessness plays a role here. I want the intention to be clear enough that a listener can sense it if they listen for it, but I also like to retain enough mystery about the process that people can experience the music in a purely somatic realm if they desire, feeling it in the body without requiring an intellectual analysis. Here lives the value of liner notes and graphic artwork to help weave a context around the music, so we can gently direct a listener’s expectation and help them uncover some of the intention of the music. I don’t feel a need for the listener to think I’m tracing my finger over a map or counting the collisions in a particle accelerator.