Part 1

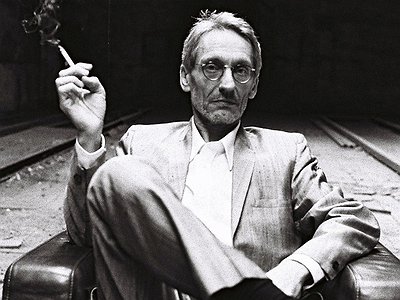

Name: Manuel Göttsching

Occupation: Guitarist, composer

Nationality: German

Current release: Manuel Göttsching just re-released a 50th anniversary vinyl edition of Schwingungen on his own label, MG Arts. The album comes as a 180g gatefold LP which also includes the original press release. Get your copy here.

The drive for perfection is not uniquely German. But, as Manuel Göttsching knows quite well, there is certainly a tendency here to regard hard work as a prerequisite for success. This ideal doesn't just relate to cars, but is typically applied to creativity as well. Unless something is intensely laboured over, honed and fine-tuned for months or years, and unless it almost causes the artist to collapse over the hardships of creation, it can be many things – a side thought, a pleasant divertissement, "mere" entertainment. Meaningful and life-changing, however, is something it could never be.

It is easy to see why Göttsching's E2-E4, recorded in late 1981, met with so little enthusiasm at home, that it would take three full years before it got published at all. The piece, a one hour long studio improvisation for electronics and guitar, was, as Göttsching remembers in this interview, realised in just one hour. Its dream-like flow, the liquid touch of the guitar and the hypnotic stoicism of its rhythmic elements made it seem, to the guardians of taste, like a throw-away experiment. Even by 1984, when it did eventually appear in record stores in a very limited first print-run, local critics ridiculed it – and it would take for dancefloors across the ocean to set the record straight.

But then Göttsching wasn't the only one to encounter this reaction. And E2-E4 wasn't the first time he'd encountered it either. The music commonly referred to as Krautrock, for which his band Ashra acted as one of the figureheads, came as a shock to the German establishment. This explains why, to this day, it still enjoys a higher profile in countries like the UK, the USA or France, than it does in its place of origin. There was a great deal of snobbery involved for sure: With very few exceptions, none of its protagonists had enjoyed a classical education. Some of them were, instrumentally speaking, diletantes at best. The albums they released did not sound polished, vocal and instrumental intonation could be shakey and the LPs were frequently distributed through small, independent labels. To many at the time – curiously from a 21st century perspective – they did not even appear to be progressive in the same sense that bands like Yes were. What could anyone possible draw from this music?

As Ashra's Schwingungen proves, quite a lot. Released in 1972, and featuring the line-up of Manuel Göttsching, Hartmut Enke, Wolfgang Müller (on drums, after Klaus Schulze had left for a solo career), and a variety of guests, the album was one of the very first significant semblances of the scene. Much more than the other “big” albums of this year – Tangerine Dream's Zeit, Klaus Schulze's Irrlicht, Can's Ege Bamyasi, Popol Vuh's Hosianna Mantra, Neu!'s debut – their vision was not so much naïve as it was an otherworldly fusion. Their background in psychedelic rock and psychedelica showed more openly, similar to the way it had on Tangerine Dream's Pink-Floyd-indebted Electronic Meditation. But it was now embedded into alien sound worlds which pointed to something far beyond these influences.

This is most apparent on the 19-minute title track, which takes up the entirety of the B-Side. The music rises slowly, as if awakening from a slumber, from a bed of ghostly yet tender sonic palpatations at the cusp of the audibility (processed recordings of Müller's vibraphones). Although working with similar equipment, the difference with the cosmic tendencies of their Krautrock contemporaries couldn't be more obvious: This wasn't cosmic music, which aimed for the stars. It was inward-looking, searching, filled with questions, doubts and fears. As would be the case with later albums, there is something about the mood of these pieces which escapes categorisation. Titles like "Light: Look at Your Sun" and "Darkness: Flowers Must Die" create opposites without ever fully resolving them.

The montage-techniques used to shape long jams and improvisations into strangely coherent compositions must have added to the stern refusal of the elite at home. But they are precisely what make this music timeless. When Manuel Göttsching sits down to record a piece of music, the preparation has been done – burned into his mind, his practise or in the tools assembled to bring it about. But as soon as he presses record, there is nothing but himself and this unique moment, which will never return the same way again. There are no trials or takes – magic happens or it doesn't. Thankfully for the listener, the latter has tended to outweigh the former over the 50 years that followed Schwingungen. And that, in a way that critics at the time could never have envisioned, makes it perfect in its own right.

This interview was originally conducted in 2006 for 15 Question's former sister publication tokafi. The version presented here has been newly edited without changing any of the original content. Just shortly before publication, we found out about Manuel's unexpected passing at the age of 70. We hope that this interview serves as a reminder about the versatility of an artist who inspired several generations of musicians from many different genres.

If you enjoyed this interview with Manuel Göttsching, visit his official website which contains a wealth of information, a complete discography and his webstore.

E2-E4

Manuel Göttsching: E2-E4 is still one of my favourite pieces, maybe my most influential one. I was very happy to perform it with ZEIKRATZER, an orchestra, and with completely different instruments. The result is a kind of (nearly) “unplugged” version. This only proves once again that E2-E4 is a very flexible composition, which can be performed in various ways, simply a very good piece of music. For a great piece of music, you have to have the right moment and catch it before it’s gone: E2-E4 was played in one evening, in just one hour.

On the other hand, Inventions for Electric Guitar took about three or four months, New Age of Earth the same. But this was a different situation, as I worked on certain techniques for these two productions. I had my own studio where I lived, so my studio was my home. That has remained to be the case until today. When I work in other studios I am open-minded. While working with Klaus Schulze or Santos it was without many preparations, just out of the blue. For some other projects I prepared the compositions in my studio, finishing them elsewhere.

I tend to make things easy, therefore I need to be well prepared. That means having a programme, to know what I want, so I have not to argue or to discuss but use the studio just as the proper technical facility to achieve what I have planed. The basic work I always prefer to do in my own studio.

Development, Influences & Inspirations

My life is music. And my music is my character. I don't know if this is different from other artists. Either way, I am a child of my generation. This is a part of the development of my music – the music I listened to in the 50s, the music I listened to in the 60s, the development of music in Germany, the revolts of 68, progressive music, Beatniks, Underground, counter culture and the efforts of doing everything differently. These were the times in which I dealt with music intensively, in which I thought about myself, my music and how I could express myself through it.

This process still continues until the present day. The difference being that external inspiration has become less important. It was those first years, when I just set out to create music, between the age of 10 and 30, that were most influential. Which is not to say that my development has frozen. But I am not influenced by tiny details as much as I used to.

~

I really can’t tell who influenced me most. I listened to the radio a lot as a child – operas for example, but also American music, early soul. Then, in the 60s, the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, beat music over all. At one time, I took a strong interest in Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix and other blues guitarists, because I had just started playing the classical guitar, but knew close to nothing about its electric pendant. I therefore wanted to find out, what other people did. Eric Clapton and his band “Cream” were a good example, because they engaged in long improvisations during concerts and then went on to release them. I just listened to those again and again, and tried to play along. It was a little harder to actually find out what Jimi Hendrix was playing, because he could bend the strings in such an incredible way. But those were my role models for practise. Still today, if someone were to give me the position of artistic director at a festival, I would invite (posthumously) Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Erik Satie, Beethoven.

Only rarely would scores of beat- and pop music be available, hardly ever of those immeasurably long improvisations. I therefore had to listen to the music and keep trying until I had managed to find the answers to my questions. I was about 16 at the time. Of course, I wasn’t planning on becoming a perfect imitator. But at least I could learn how to do this, in order to develop something entirely different later on.

~

I’ve always had difficulties with Jazz. To me, it was an old-fashioned kind of music. What I associated typically with Jazz were old men with beer-bellies and beards, who would meet at ten o’clock in the morning on a Sunday for brunch and then then start swinging. I felt slightly repulsed by this. Of course, this was hardly real Jazz, but rather its nemesis. Over time, Jazz has diversified extremely. There was Free Jazz, Cool Jazz and Jazzrock.

An important factor has also been that the guitar only played a secondary role in Jazz, when compared with the winds – it was more of a rhythm instrument. Jazz originates from a time when the guitar was not amplified and therefore not a dominant instrument. This would gradually change.

Originally, the guitar was a very quiet instrument, simple but effective, which could be used for polyphonic accompaniment and as a solo instrument. Franz Schubert, for example, composed all of his pieces on the guitar, simply because he could not afford a piano. It was only until the guitar was upgraded with the famous “pickup” that it received an entirely different dimension – and this counted for Jazz as well, only that the cards had already been dealt. You simply couldn’t lay off all those horns.

Later, Jazz guitarists like McLaughlin and Al di Meola turned up. They never really convinced me, because it was rather the speed of their fingers than the brilliance of their music which was impressive. Paco de Lucia is a different story, because he adds some traditional (Spanish) elements. The guitar gets along better with the Blues. Rock n Roll and later Rock Music, up and until Metal, are just the logical progression - faster, harder and most important of all: louder.

In fact, I played in a blues band until I was 16, 1968/69. Until this very day, Blues elements can repeatedly be found in my music.

Performing Live

For a good live performance, I like to feel fresh, well-rested and in good spirits. I can only talk about my own performance: What I like to do, is play vivid and lively music. Depending on the occasion (for example when playing film music), there can be slightly more or slightly less “form”. The concept can have been prepared a long time beforehand or develop intuitively from the moment. The only thing that matters is that the performance is open. If too much is programmed and practised, you risk loosing any kind of real ambiance, because the sole thing you do is to try and avoid mistakes.

To me, a good concert always involves a few askew notes, which were not part of the program. It is these notes that make the whole thing lively and unique.