Name: Sudhu Tewari

Nationality: American

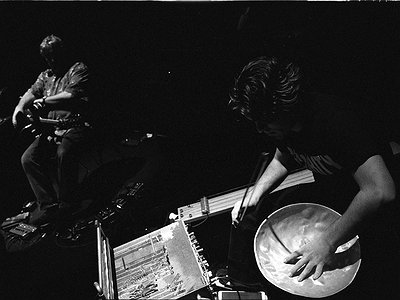

Occupation: Composer, improviser, sound artist, instrument builder

Current release: Sudhu Tewari teams up with Fred Frith for Moving Parts, out via Theresa Wong's fo’c’sle imprint.

[Read our Theresa Wong interview]

[Read our Fred Frith interview]

If you enjoyed this Sudhu Tewari interview, and would like to find out more about his music, visit his official homepage. He is also on Instagram.

What were some of your earliest collaborations? How do you look back on them with hindsight?

In college I was paired up with a guy I thought I had nothing in common with. I resented the enforced collaboration and prepared for battles of will and opposing aesthetic senses.

I was totally wrong. Somehow, thankfully, I dropped my defensive preconceptions and it was a fruitful and productive collaboration. We worked together for years after that!

How do you feel your sense of identity influences your collaborations? Do you feel as though you are able to express yourself more fully in solo mode or, conversely, through the interaction with other musicians? Are you “gaining” or “sacrificing” something in a collaboration?

I think I gain a great deal in collaboration. Left to my own devices I’d likely plan and ruminate and evaluate (research, prepare, experiment, etc) and never finish anything.

Collaborators bring along with them the all-powerful notion of the deadline! I feel a sense of responsibility to my collaborators to deliver what I promise, which inspires and motivates me.

When did you first start getting interested in musical improvisation?

I made ‘the switch’ from seeing myself as a tape music composer to improvisor about halfway through my studies at Mills College (largely the result of experiences with the illustrious Fred Frith).

I was oppressing myself with the rigors of tape composition (each microsecond had to be perfect) and longed for an expressive outlet. Improvisation offered that, with the caveat that building my own instruments seemed necessary to free myself from existing traditions.

Which artists, approaches, albums or performances involving prominent use of improvisation captured your imagination in the beginning?

Improvisation has always been a part of my life. My father was a Hindustani vocalist, so my experience was that it was normal for several musicians meet for the first time on stage and play a lengthy concert together, interacting with each other as if they’d known each other for years.

For me, the idea of improvising with someone you’ve never spoken with has never been unusual. I only recently realized that not everyone takes this for granted!

Focusing on improvisation can be an incisive transition. Aside from musical considerations, there can also be personal motivations for looking for alternatives. Was this the case for you, and if so, in which way?

Very much so. I felt constrained by the rigidity of the Hindustani and Western classical traditions in which I was raised and was later even more so constrained by my own perfectionism in creating tape music.

Improvisation was a way for me to free myself of those constraints (though I’ve found plenty of hang ups there as well).

What, would you say, are the key ideas behind your approach to improvisation? Do you see yourself as part of a tradition or historic lineage?

I suppose I see myself in the Frith-ian lineage! I came to appreciate Fred’s approaches because they seemed natural to me—the pedagogy wasn’t so much taught as lived.

I think that’s as much a tradition as any codified methodologies teaching specific sorts of improvisation techniques.

Can you talk about a work, event or performance in your career that's particularly dear to you? Why does it feel special to you? When, why and how did you start working on it, what were some of the motivations and ideas behind it?

This collaboration with Fred, the band Normal, and specifically our project to create a fleet of instruments together, is especially dear to me.

We started playing together 20 years ago just after I graduated from Mills where I’d harangued Fred for an ‘improvisation lesson’. I think he thought it was a bit of a ridiculous idea and kept dodging my requests but proposed instead that I book us a concert and we’d play together on stage. I did and we did and the rest is history.

We’ve never rehearsed which probably keeps it fresh and interesting for us. Apparently, I inspired Fred to bring his homemade instruments out of the closet which in turn inspired me to continue on the path of making instruments (and my quest to improve my skills as an instrument builder).

Before you started making music together, did you in any form exchange concrete ideas, goals, or strategies? Generally speaking, what are your preferences when it comes to planning vs spontaneity in a collaboration?

It’s a balance. Too much planning gets in the way of actually doing anything. Rushing straight into doing without a plan can yield half-baked results but, for me, it’s often about overcoming inertia. Something has to happen to get started. If it’s terrible, then that’s something to push off from. If it’s promising, we’ve identified a potential direction in which to continue.

For this project I had some concrete goals and I’m sure we discussed them. Then the circumstances changed and so did the goals. Many specifics gave way to “let’s make some instruments, play them, and then modify them to suit our needs (or adapt our playing to take advantage of what the new instruments make available to us).”

I’m typically sceptical of planning as it often assumes that we know more than we do; that somehow we’ve identified exactly what we need and we can proceed to realize our vision. More honest, I think, is to acknowledge that we have no idea what we’re doing but by remaining open to possibilities we can find really amazing things that we never would have thought of on our own.

Describe the process of working together, please. What was different from your expectations and what did the other add to the music? How did this particular collaboration come about?

Our latest flavour of collaboration has been quite fruitful: Fred and I were commissioned (by the Center for New Music’s Window Gallery—a gallery that showcases the work of experimental instrument builders) to build a fleet of instruments for us to play. The concept was wide open: just build instruments, no other specified intent or end result.

I was also coming out of writing my dissertation on Tom Nunn, a prolific and influential San Francisco-based instrument builder, with whom I’d had lengthy discussions about the ideals of instrument building and the criteria with which to assess the success of invented instruments. I wanted to build easy-to-play, modular instruments that would be easy to transport, envisioning a world tour with a gang of great musicians playing composed and improvised music on them.

Leading up to the project I purchased a collection of things I thought we might need, parts for building instruments into travel cases, guitar pickups, and a slew of accessories. I figured Fred might like to rebuild or revisit some of his home-mades from the 80s and I was interested in exploring guitar pickups as a means of amplifying (and eventually processing) the sounds created by small-ish modular ‘devices’. I’ve been using contact microphones (piezo pickups) for years and, while they’re incredibly useful, I wanted to explore other, less tactile, pickup options.

We went about our lives, knowing that this fun collaboration lay in our future, then the pandemic hit and everything shifted. Then it shifted a little more. Working in the pandemic meant that travel was out of the question, so I quit worrying about portability and decided to work on some other things I’d wanted to try out. With Fred being a string player I thought I’d make some cool stringed instruments to see what he would do with them, especially if the strings were much longer than those of a typical guitar. I also began to embrace the idea of building instruments for someone else to play, a different kind of design challenge and also what a treat to not have to be the one to practice and develop the necessary playing techniques!

Not everything we tried was a success. The Post Hole Tone Music Box evolved from an experiment to use tuned holes to make an instrument. It was a great idea that needed far more time and energy to pull it into a playable form than was warranted by the sounds it produced. Other instruments, such as the No Strings Guitar, started as a test bed for a simple idea that evolved into a terribly promising platform to be developed further.

I’ve also been working on a particularly promising collaboration with percussionist Jordan Glenn and his ensemble BEAK. Jordan had some interesting ideas for instruments that I’ve enjoyed building, it’s great to be able to simply focus on execution without having to also come up with the idea. I’ve also very much enjoyed being able hand off instruments that I’ve built for him to compose for. These “punts” have resulted in some new material for the ensemble and I’m thrilled to see my instruments put to use in a manner I would never have been able to manage.

When you're improvising, does it actually feel like you're inventing something on the spot – or are you inventively re-arranging patterns from preparations, practise or previous performances?

Oof! This is a huge struggle for me. I‘m less interested in things I’m already familiar with, so I’m constantly searching for the new and exciting. That said, the search leading to the new and exciting isn’t always interesting to listen to! But when it results in something captivating, then it becomes worth it, and the moment when it arrives is glorious, in part because we’ve shared the journey.

Practice means developing skills on an instrument and developing ‘things’ I can do (involving particular playing techniques, configurations of electronic effects, or combinations). But in performance it’s a constant struggle to stay in the moment and not just imitate myself enjoying a moment that I found in the past.

Practicing how to make quick changes and smooth transitions can be useful, but I also value spontaneity (perhaps even more than adequate preparation). I love sharing the joy of a new discovery with an audience.

To you, are there rules in improvisation? If so, what kind of rules are these?

There are only rules if you choose to establish and abide by them (perhaps this goes without saying). To me improvisation is less about rules, and more about common courtesy (especially when playing with someone for the first time).

But also, polite conversations aren’t typically that interesting or engaging—they are, more often than not, formulaic and shallow. I think the music develops as playing relationships become more intimate and we feel more comfortable disregarding common courtesies in favour of digging deeper.

I value honesty and authenticity over propriety. If an honest conversation breaks rules, then so be it.

Derek Bailey defined improvising as the search for material which is endlessly transformable. Regardless of whether or not you agree with his perspective, what kind of materials have turned to be particularly transformable and stimulating for you?

Melody! What a wonderful thing! A few notes, not really many at all, repeated and carefully placed. I’ve often focused on particularly delicious sounds, each unique in its flavour, and considered sequences of these sounds to play the role of traditional melody (sequences of pitch with little timbral variation). But, recently I’ve come to appreciate the traditional definition of melody, in which the variety comes only from pitch. What a concept!

Nothing new in music, but something I’ve recently come to appreciate anew.

In a live situation, decisions between creatives often work without words. How does this process work – and how does it change your performance compared to a solo performance?

One of the things that I absolutely LOVE about working with Fred is that there’s a great deal that we don’t discuss! We just let it happen! The music is just there, happening, and words often just get in the way.

Strangely enough we often align in the weirdest ways. More than once, after a concert together, I’ve shared some strange process I chose to follow during the performance and Fred will reveal that he’d also chosen to follow a similar process. It’s spooky.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? In which way is it different between your solo work and collaborations?

In my creative state I’m non-verbal. When working solo I can move at my own speed, whatever that might be. When engaging with a collaborator I have to flip an internal switch to turn the words back on and run the system more slowly to allow for the words to catch up with the thoughts. At times that can be frustrating! Alternately, at the slower speed, thoughts benefit from the scrutiny of more than one mind and there’s more time for adequate consideration.

I suppose one can treat everything like a collaboration, even between different aspects of oneself when working solo, and that has the benefit of ‘adequate consideration’. But working free of constraints means just letting it happen and the magic of the moment can deliver more than any amount of consideration.

The ideal state for creativity is thus: having gotten out of my own way.

Was this collaboration fun – does it need to be?

Working with Fred is always fun! And, yes, collaboration should be fun!

Sure, sometimes collaboration can be tough, but there are often great benefits to working through difficulties, and even that can be considered fun when the results are worth it!!

What are your thoughts on the need for compromise vs standing by one's convictions? How did you resolve potential disagreements in this collaboration?

I’m always right. Nuf said.