Part 2

Could you describe your creative process on the basis of a piece or album that's particularly dear to you, please? Where did the ideas come from, how were they transformed in your mind, what did you start with and how do you refine these beginnings into the finished work of art?

In late 2017, when I started working on what would become my new album Cream Parade, I wanted to do something extremely dry, to get rid of a certain lyricism that I inherited from jazz from the 40s through to the 60s. I prepared a number of different electronic beats based on a marching-band snare and mixed it with sequences from a small, monophonic synthesizer, in order to avoid chords. Within a few days, I recorded something like 30 different sketches. After that, I organised the sequences into different parts to create song structures and then recorded myself improvising some vocals.

This generated 12 tracks. It was good overall but felt a bit too robotic, too Kraftwerkian to me, so in December I called Nyllo Canella, a Brazilian percussionist I had just met, and he recorded percussion on all of the songs. It was more organic, but the songs weren’t rich enough, so I added field recordings. But something was still missing. Guitar didn’t work. I still wanted to avoid chords. I was desperate, so I tried using one of the most horrible sounds I could think of, the Ableton hairstylist clubber preset. It had an immediate impact. It was as if the marching-band groove and drum sequences had always been waiting for their Eurodance riffs. Suddenly, it was the most beautiful music in the world.

When the euphoria subsided, I noticed I made that classic mistake while wearing the producer-composer hat: my vocals were terrible. In April, I booked a few hours in a Berlin studio with a ribbon mic and a condenser. I recorded a calmer version of the lead vocals as well as my speciality: castrato backing vocals. I was sounding pretty good, but then, for the first time in my life, I developed an unexpected little complex about my French accent and couldn’t stand hearing my songs in English anymore. The owner of the studio knew a singer who was British but knew French. The idea hit me: if we'd both sing in French and in English, we could form this hybrid foreign-native accent vocal duo. So, Heidi Heidelberg came to the studio for a couple of hours and sang on three songs.

There was still a small problem. It was all very dry, emotionally – which is what I wanted initially – but I started to feel a bit like when you move to a new country, you randomly start missing all the stuff you never liked before. I was suddenly convinced that the overall purpose of this album was to hear occasional fragments of sentimentality. I asked my favorite saxophone player, Greg Tirtiaux, to play on half of the songs.

Mixing: I don’t like doing it myself, but I also don't enjoy rediscovering my songs loaded with reverb, phaser or whatever weird fantasy some sound engineer tries to explore behind your back. It can be hard to find the right person, but that July, I heard the latest album by Chris Imler, mixed by Dirk Driesselhaus – Schneider TM – and contacted him straight away. Dirk did an amazing job on Cream Parade. He kept the spirit of my premix but made the sounds of the different elements perfectly calibrated – airy and no longer tiring. Beautiful sonic architecture that really augmented my arrangements. For mastering, especially if you live in Berlin, Rashad Becker is known as a god. I went to him, and the results are spectacular, especially the sub bass.

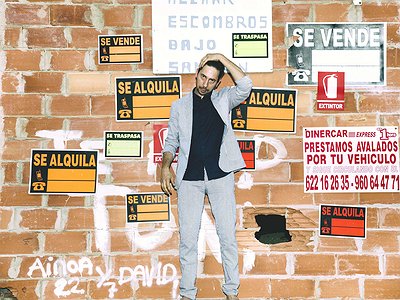

Then it was wintertime already, meaning time to migrate to Spain. That’s where we did all the visual aspects – the artwork and music videos, with Arnau Pascual Ledesma and Systaime.

There are many descriptions of the ideal state of mind for being creative. What is it like for you? What supports this ideal state of mind and what are distractions? Are there strategies to enter into this state more easily?

This remains a mystery to me. I noticed that at certain times of the day, my brain works differently, and ideas flow better – usually in the evening. I think that the biggest trick for composing is to be mentally fresh at the moment of writing, and to work fast. This requires some preparation beforehand. For me, that means choosing sounds, rhythms, samples and deciding on concepts and limitations.

How is playing live and writing music in the studio connected? What do you achieve and draw from each experience personally? How do you see the relationship between improvisation and composition in this regard?

They clearly feed off each other. The problem with composition is that you’re alone in a room full of fantasy. You can think that you’re Mozart or Bon Jovi, and nobody will be there to contradict you.

Once you introduce your stuff to the outside world, in general, nothing happens as you'd imagined. Playing live is a complex equation between many different parameters, and unfortunately for us, the audience changes the meaning of what we do. For the post-romantic, individualist super-geniuses that we are, it’s horrible to hear this, but the audience is actually the co-composer of the music. They have the power to truly change the meaning of what you play. Horrible bands can become divinity, and vice versa. That’s why I think the best performers come on stage well prepared but without any pre-planned intention. Being charismatic helps too, of course.

One of the biggest problems with 20th-century European classical music is that many composers didn't play their own music live. They focused on writing and left the performance to the players. A lot of compositions looked like perfect plots on paper but were real garbage once performed live, especially after the 60s. And being in a position where you're always able to say that it's the fault of the players or the audience, or capitalism, doesn’t help, either.

How do you see the relationship between the 'sound' aspects of music and the 'composition' aspects? How do you work with sound and timbre to meet certain production ideas and in which way can certain sounds already take on compositional qualities?

The interesting thing I discovered when I started making electronic music is that, compared with acoustic music – I used to perform my work with classical players –you don’t think so much about harmony.

Right before my band turned into my computer, harmony was a big problem for me. Everything I was writing sounded old to me.

Looking back, I think I was simply facing a similar problem to the those 20th-century composers. Just like them, I wanted to abandon expression, and harmony wouldn’t let me do it. Electronic music has been my John Cage, a liberation. I started thinking in terms of sound rather than chords. Sound, in this case, is completely integrated in composition – it’s not an extra step.

Our sense of hearing shares intriguing connections to other senses. From your experience, what are some of the most inspiring overlaps between different senses - and what do they tell us about the way our senses work? What happens to sound at its outermost borders?

I’m synaesthetic. I see colors when I hear music, so there's a natural multimedia relationship for me, because it’s all already in my head. What happens in your brain or body when you’re affected by the music you’re hearing is a real mystery. I love narrative music, but also very abstract music, and they both clearly affect different parts of the brain.

Art can be a purpose in its own right, but it can also directly feed back into everyday life, take on a social and political role and lead to more engagement. Can you describe your approach to art and being an artist?

This is a tricky one. I think art is overrated as a political tool – I don’t think it affects politics much. Stuff like “Imagine” by John Lennon is completely useless, if not dangerous, because it makes people think that they all agree whereas they actually don’t.

At the moment, the worst use of politics in art I can think of comes from theatre or contemporary art, where in order to get funding or to sound deep, artists often talk about problems that don’t really concern them. It’s a way of attaining a moral authority that I particularly dislike. It seems to declare: Since my political convictions are fair, my work is unattackable. Art has nothing to do with this. Despite all of the attempts otherwise in the 20th century, art is about expression, after all. As we’ve seen many times, like with Jean-Louis Costes or Momus, an artist suddenly revealing the little Nazi or abuser living inside of him has can be far more insightful than someone informing us that war and rape are bad.

This being said, there are political elements in my stuff, too. I just try to let it surface without planning it, despite somehow being present, as the narrator of the song, for example.

It is remarkable, in a way, that we have arrived in the 21st century with the basic concept of music still intact. Do you have a vision of music, an idea of what music could be beyond its current form?

I’m not so sure that the basic concept is how it used to be. If you look at the different genres of music, I don’t think that so-called experimental music existed before John Cage, for example. Of course, humans in the past could also sense and appreciate pure sound, but I can hardly imagine people in Jesus' time spending six hours listening to the equivalent of a Morton Feldman string quartet or M.E.V. jamming or Xenakis at a barbecue.

One change that's maybe important is the idea of progress in art; modernism, the permanent revolution. It became an old-fashioned idea. But I think that strangely, post-modernism has also reached its limit with the Internet. As we're saturated with information, we're forced re-organise things in a clearer and less superficial way, non-accumulative.

I have the impression that what will make sense going into the future is a more organic and collective music, with many co-authors – not necessarily in the signature, but in the creation and construction of the music. We are already seeing this with samples, appropriations, using existing material or even complete songs, in order to produce something that makes sense for a community rather than an individual genius. Something in which context is at least as important as content.