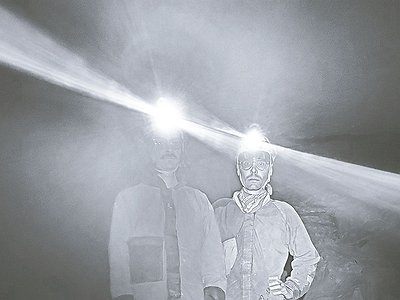

Name: Mont Analogue

Members: Alex van Pelt, Ben Lupus

Nationality: French

Current release: Mont Analogue's Faire fleurir EP is out via Kidderminster.

If you enjoyed this Mont Analogue interview and would like to stay up to date with the band and their music, visit the group on Instagram, Facebook, Soundcloud, and twitter.

When I listen to music, I see shapes, objects and colours. What happens in your body when you're listening? Do you listen with your eyes open or closed?

Ben: Mostly open, because I fall asleep pretty easily when my eyes are shut, and I hate listening to music while sleeping.

I don’t think I project anything onto music. I don’t tell stories to myself (I do when I write music though), it all happens on the subconscious level. Of course, some albums or tracks bring up strong memories, sometimes in the form of bodily sensations.

Alex: I feel like some chord progressions make my body feel warm and my brain cells go wild! The music that seems appealing to me does not have clearly delineated shapes but is a blurry vision of colors. Not really in a synaesthetic way but more like a painting that I can feel beneath my skin.

How do listening with headphones and listening through a stereo system change your experience of sound and music?

Ben: We spend a lot of time creating music for theatre and dance projects, so we have access to big sound systems, outside of a live situation with an audience. The way the music resonates sometimes, how it fills the room - this is the best, and I think this kind of experiences definitely shaped our music.

Studios, control rooms equipped with very good speakers, have been a good way to experience music as well - a privileged way. The truth is that most of my listening time still happens through shitty Iphone earplugs, and I like music just the same.

Tell me about some of the albums or artists that you love specifically for their sound, please.

Ben: Soundwise, and everything else wise, The Inheritors by James Holden is forever a touchstone, at least for me.

Recently I’ve been really interested in Raül Refree’s work, both as a musician and a producer.

And I have been really moved by Hana Stretton’s Soon, …

... as well as Peter Brotzman & Han Bennink’s Schwarzwaldfahrt. Both share a «recording in the wild» dimension, which I’m really into right now.

Alex: I think Harmonia and Cluster are really important to me in the way their sounds are filtered and velvety. I’m also really into Lorenzo Senni's supersaws (my favorite track is «the shape of trance to come») and 7038634357 («no hate is a cold star») for a more digital approach to electronic music.

I think those four make a pretty decent map of sounds I like and try to emulate and explore while playing with Mont Analogue.

[Read our Hans-Joachim Roedelius of Cluster and Harmonia interview]

[Read our Hans Joachim Roedelius interview about Ego as an Energy]

[Read our Roedelius & Tim Story interview about Collaboration]

[Read our Michael Rother of Harmonia interview]

[Read our Michael Rother interview about Improvisation]

[Read our Brian Eno interview feature about Climate Change]

Ben: As a band, I would say Jon Hassell’s approach to sound and composition is something we constantly come back to.

Mica Levi’s soundtrack to Under The Skin, as well as Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow’s Annihilation, have both been constant references in the making of our last record.

Faire Fleurir is the studio version of the live score to a contemporary dance piece by Nicolas Fayol. We’re big fans of soundtracks: they’re a great exercise in balance between abstract & narrative, sound design & composition.

Do you experience strong emotional responses towards certain sounds? If so, what kind of sounds are these and do you have an explanation about the reasons for these responses?

Ben: I really don’t know why but I love crackling noises, humming electricity, crispy high ends. When these kind of components enter a musical piece, there is a good chance I’m going to like it.

Texture is always so important to me. "Xylo," by Yves de Mey, is a good illustration of that.

[Read our Yves de Mey interview]

Alex: As I said before, filtered machine drums and supersaw synths!

There can be sounds which feel highly irritating to us and then there are others we could gladly listen to for hours. Do you have examples for either one or both of these?

Ben: It’s all very common I think: running water, birds, wind … natural sounds in general feel very good. I live above a primary school, and the noise the kids make in the playground is a very comforting one to me - the sound of the comfort of domestic life I guess …

On the other end, my upstairs neighbour blasting French musicals and singing to them is a very very annoying sound. Phones vibrating irritate me a lot, they are very stressful I think.

Alex: I live in Paris, and city noises are both annoying and a beautiful symphony depending on my mood.

Are there everyday places, spaces, or devices which intrigue you by the way they sound? Which are these?

Ben: I heard my mother’s electric toothbrush the other day. It hums in a very specific way, I thought it would make for a very nice oscillator.

Have you ever been in spaces with extreme sonic characteristics, such as anechoic chambers or caves? What was the experience like?

Ben: We actually went into a cave to record some sounds for the new record. Most of them didn’t make the cut, but the overall atmosphere (and how we experienced it) was crucial in the process. The track “Castelbouc n3” is named after this cave.

Do music and sound feel “material” to you? Does working with sound feel like you're sculpting or shaping something?

Ben: Definitely. Sound sculpture is more than just a metaphor, it is a vivid sensation, and we always keep refering to it while talking to each other about whatever we are currently working on.

How important is sound for our overall well-being and in how far do you feel the "acoustic health" of a society or environment is reflective of its overall health?

Ben: I think it is very important, and systematically overlooked, when not openly ignored. Access to a healthy acoustic environment, at work and at home should be granted to all, as the lack of it can lead to serious conditions.

And access to silence, or at least to spaces free of any human made noises, is really important too.

Sound, song, and rhythm are all around us, from animal noises to the waves of the ocean. What, if any, are some of the most moving experiences you've had with these non-human-made sounds?

Ben: My best memory of this kind is of being in a forest one sunny winter morning, with the snow melting from the pine trees, drop after drop, and everything else totally still. I stood there listening to the music for a while, it was beautiful. I have tried many times to recapture such a moment on tape, and never achieved it yet.

Alex: I’ve just spent a week in Britanny at a friend’s house that’s literally by the ocean. There has been a big storm, and the sounds of the waves, the wind and the rain all mixed up together created a very powerful and yet calming sonic environment.

Many animals communicate through sound. Based either on experience or intuition, do you feel as though interspecies communication is possible and important? Is there a creative element to it, would you say?

Ben: I think it is (possible, important, creative).

My father whistle to birds, and they sing back. I have witnessed entire conversations, on multiple occasions.

We can surround us with sound every second of the day. The great pianist Glenn Gould even considered this the ultimate delight. How do you see that yourself and what importance does silence hold?

Ben: I could not stand sound all day long. Silence is very important to me, it holds a power and a virtue that is really different, but not opposite. There is something religious about silence, something mystic. It is so weak, it has to be protected, cared for.

There’s barely any true silence in music, but in the spaces created by dynamics, one can hear the longing for the absence of hearing, and for the truth that comes with it. So, yeah, come on Glenn, keep quiet for a while.

Seth S. Horowitz called hearing the “universal sense” and emphasised that it was more precise and faster than any of our other senses, including vision. How would our world be different if we paid less attention to looks and listened more instead?

Ben: More audio books and less printed ones ? It’d be a shame. Books are the best.