Name: Thomas Elsner

Occupation: Art Director, designer, photographer, magazine founder and party organiser at Elaste

Nationality: German

Current release: Together with Michael Reinboth, Thomas is currently in the process of preparing a major book about the history of Elaste. For more about that project, read our Michael Reinboth interview about Elaste, Compost, and the Joy of DIY.

If you enjoyed this Thomas Elsner interview and would like to stay up to date on his work, visit the official homepage of his agency. He is also on Instagram.

How big a role did fashion play as a topic for Elaste?

The role of fashion has always been of great importance to Elaste. Our focus was particularly on presenting new trends and street fashion, although this term was not as common in the early 80s.

Elaste has always been a "pictorial book" that, alongside intelligent discourses, enjoyed showcasing stimulating and unique images, with fashion serving as a means of representation.

How big was the step from Elaste to Vogue would you say? One would assume pretty big – but then again, some of the qualities of your Elaste work must have played a part in Vogue hiring you as their art director for the mag as well.

The transition from Elaste to Vogue was tremendous in many ways. Now, I could collaborate with almost all the interesting photographers of that time. The partnership with Condé Nast immediately granted access to the world of the fashion elite.

With the then Art Director of Men's Vogue, Beda Achermann, I shared the same taste in terms of photos, and we often worked together on concepts for the magazine. Suddenly, renowned photographers like Herb Ritts, Michael Roberts, Paolo Roversi, Nick Knight, were bringing our ideas to life, and we could lay out these images.

With artists like Greg Gorman, David La Chapelle, and Norman Watson, I could even realize my own productions as an associate Art Director. Ultimately, it was probably my vision for images and my broad spectrum in layouting that led me to Condé Nast.

The content themes at Elaste were always very zeitgeisty, subcultural, and sometimes subversive. That was naturally different at Vogue, Men's Vogue, and Miss Vogue, where the themes were more situated in the luxury, lifestyle, and art realms.

Did you ever during your time at Vogue cover a topic or personality you had already covered in Elaste?

It was primarily photographers such as Mark Lebon and Ellen von Unwerth who had also contributed to Elaste. There were also overlaps in interviews or features, covering individuals such as Patsy Kensit, Jack Nicholson, or Yello, for example.

But regarding the content, I had limited influence on magazines like Vogue and Men's Vogue. I wasn't in that position. It wasn't until I became the Art Director at Miss Vogue that I actively shaped the themes.

As you can imagine, I introduced many music-related topics there, and in the fashion realm, we often featured street-fashion elements like clothing from BOY, Guess, Doc Martens, or Katharine Hamnett.

What was the relationship between music and fashion for you like personally? When was the first time that you became aware of the connection between fashion and music?

When growing up with the Beatles and the Stones, you immediately sense the connection between fashion and music.

Depending on the musical phase, the Beatles' outfits (and hairstyles) changed accordingly. From black leather to conservative suits, from Carnaby Street style through the hippie look and military style to the vagabond look with hats, beards and black coats.

David Bowie's musical evolution was also reflected in his outfits, from the London Boy to the androgynous glam rocker, from the extraterrestrial to the Thin White Duke.

What do fashion and design add to (y)our perception of music?

I definitely let myself be influenced by the visual aesthetics of artists. In the late '70s, I exclusively wanted to listen to music from menacing-looking, short-haired artists who wore punk or new-wave clothing and designed their album covers with geometric symbols, fluorescent colors, and experimental photos and typography.

I bought many records solely because of their covers, such as Suicide (Suicide),

The Clash (The Clash),

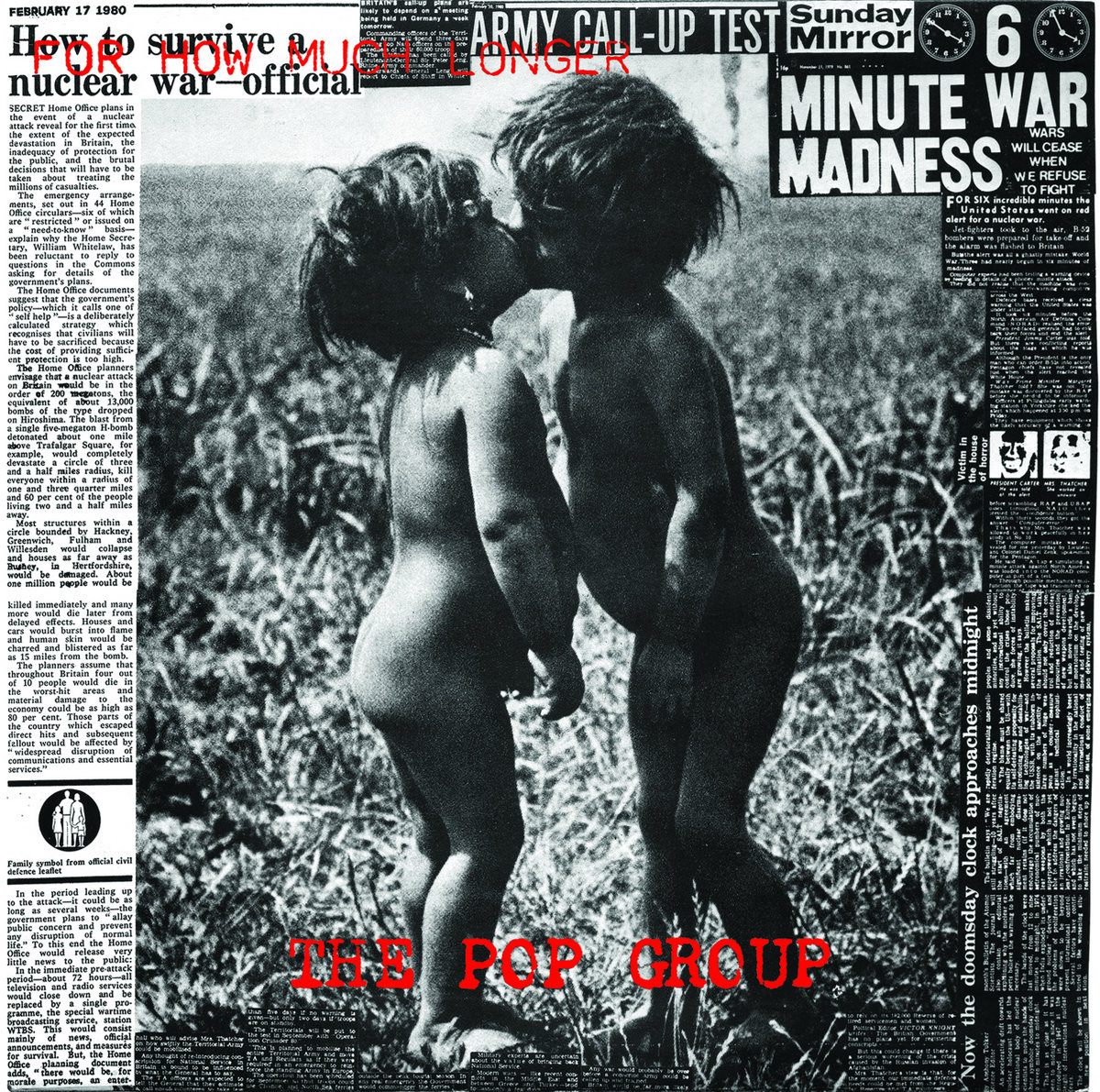

The Pop Group (For How Much Longer Do We Tolerate Mass Murder?),

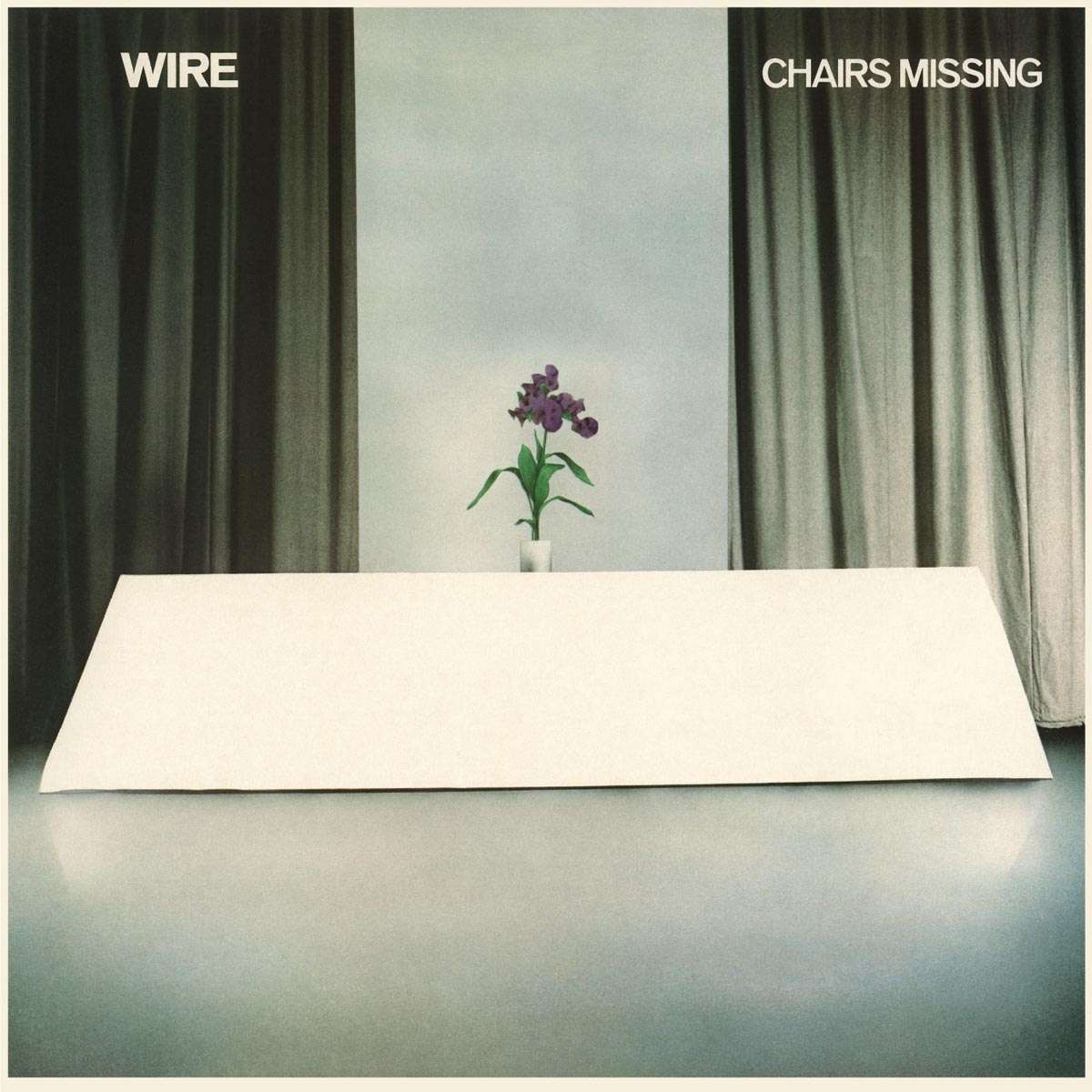

and Wire (Chairs Missing).

[Read our Gareth Sager of The Pop Group interview]

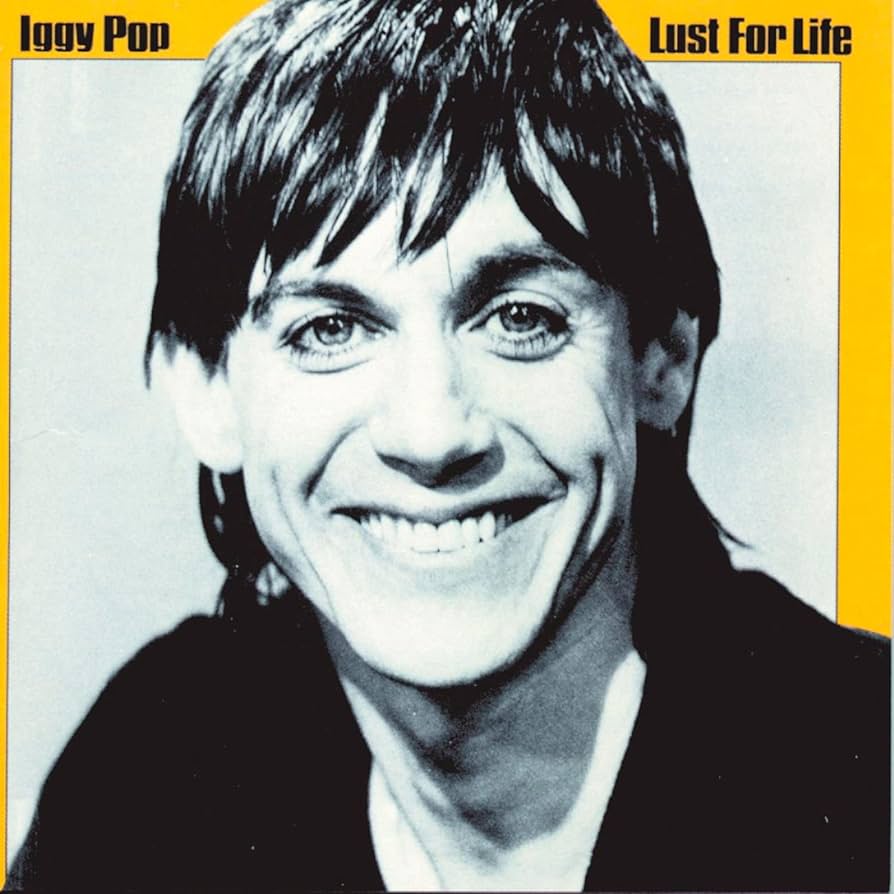

On the other hand, unattractive album covers almost deterred me from purchasing, as was the case with Iggy Pop (Lust For Life).

Interestingly, my collection includes many records whose covers were designed by Malcolm Garrett or Peter Saville. Evidently, I could deduce from this that I would also enjoy the music.

Fashion can project an image, just like music can. As such, it is part of the storytelling process. What kinds of stories are being told, would you say?

Yes, I definitely think there are overlaps. In the world of fashion and (pop) music, similar stories are often told, emphasizing specific roles and identities. Stories of rebellion and nonconformity, of individuality and visions are narrated.

Each clothing style can carry its own narrative about who we are or who we aspire to be.

What can fashion express what music can not?

While music can convey emotions and moods more directly through sounds and lyrics, fashion provides a visual platform to express identity, belonging, and style in a tangible way.

However, both art forms can merge and complement each other to make more comprehensive creative statements.

It seems obvious that fashion and music are closely linked, but just how that influence works hasn't always been clear. Would you say that music leads fashion? Is it the other way round? Or are they inseparable in some ways?

The relationship between fashion and music is often mutual and can be seen as reciprocal influence. It's not always clear whether music leads fashion or vice versa, as both areas often inspire and influence each other.

Musicians choose and combine fashion pieces, breathe life into them with their music, and give them new meaning. Faded blue jeans and cowboy boots symbolize rock, while ripped jeans and a black leather jacket are associated with punk. Tight black jeans and a black turtleneck connect with post-punk or Britpop, while baggy jeans originate from hip-hop.

The fashion industry adopts these styles, commercializes them, and passes them on to music fans. Many couturiers delve into specific music genres and interpret them, such as Raf Simons or John Galliano. The process is somewhat different for Vivienne Westwood – she took clothing from different scenes, like the fetish and protest scene or the unisex movement, deconstructed them, and created the punk look, which was then picked up by music bands.

It's challenging to separate fashion and music in their interweaving. Both are crucial expressions of culture and influence each other in diverse ways. It's more of a symbiotic relationship where both sides exchange ideas and impulses, creating a dynamic and creative interaction that can produce something new.

Creativity can reach many different corners of our lives. Do you personally feel as though designing a fashion item or even putting together a great outfit for yourself is inherently different from something like composing a piece of music?

Yes, creativity can permeate many different areas of our lives. Personally, I feel that designing a fashion item or putting together a great outfit is inherently different from composing a piece of music.

I've observed how designers work; it's more of an analytical process that draws from existing elements and then reassembles them, altering proportions and cuts. However, the final result must be wearable. Some musicians may follow a similar cut-and-paste approach, like Brian Eno, Holger Czukay, or David Bowie.

[Read our Brian Eno interview feature about climate change]

Nevertheless, I would say that the approach to music is more oriented toward feelings, melody, rhythm, and attitude. It can be freer and more abstract than fashion, as it's not based on physical materials but only on sound waves.